Bluebird Grain Farms staff writer

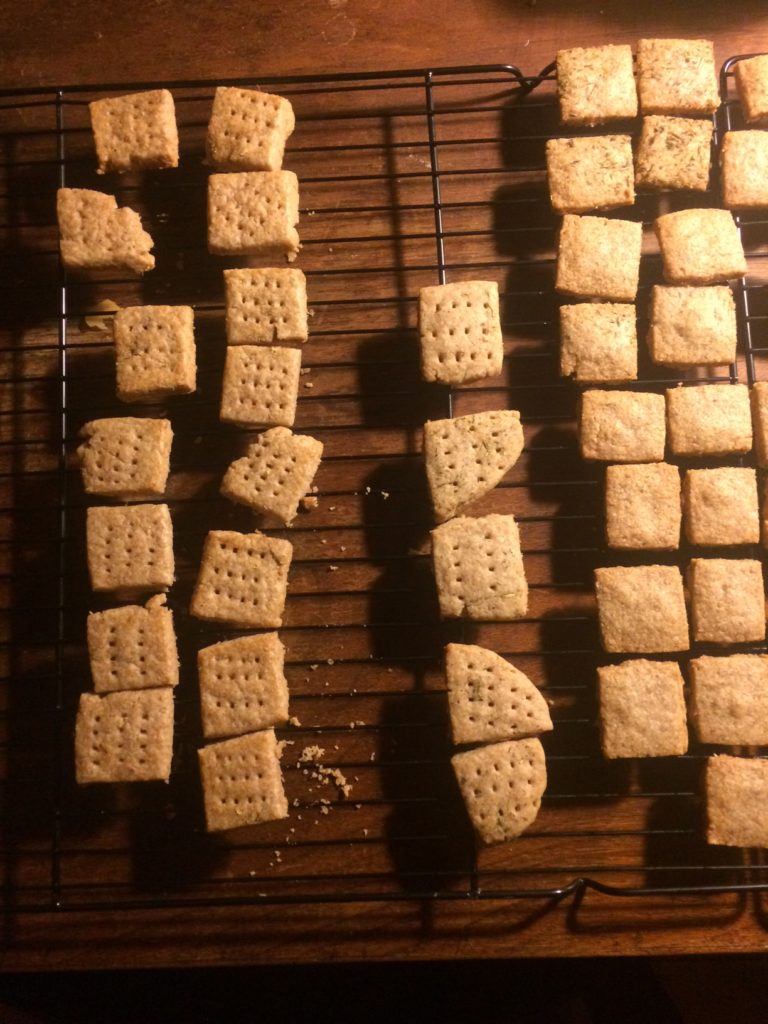

photos courtesy of Amy Halloran

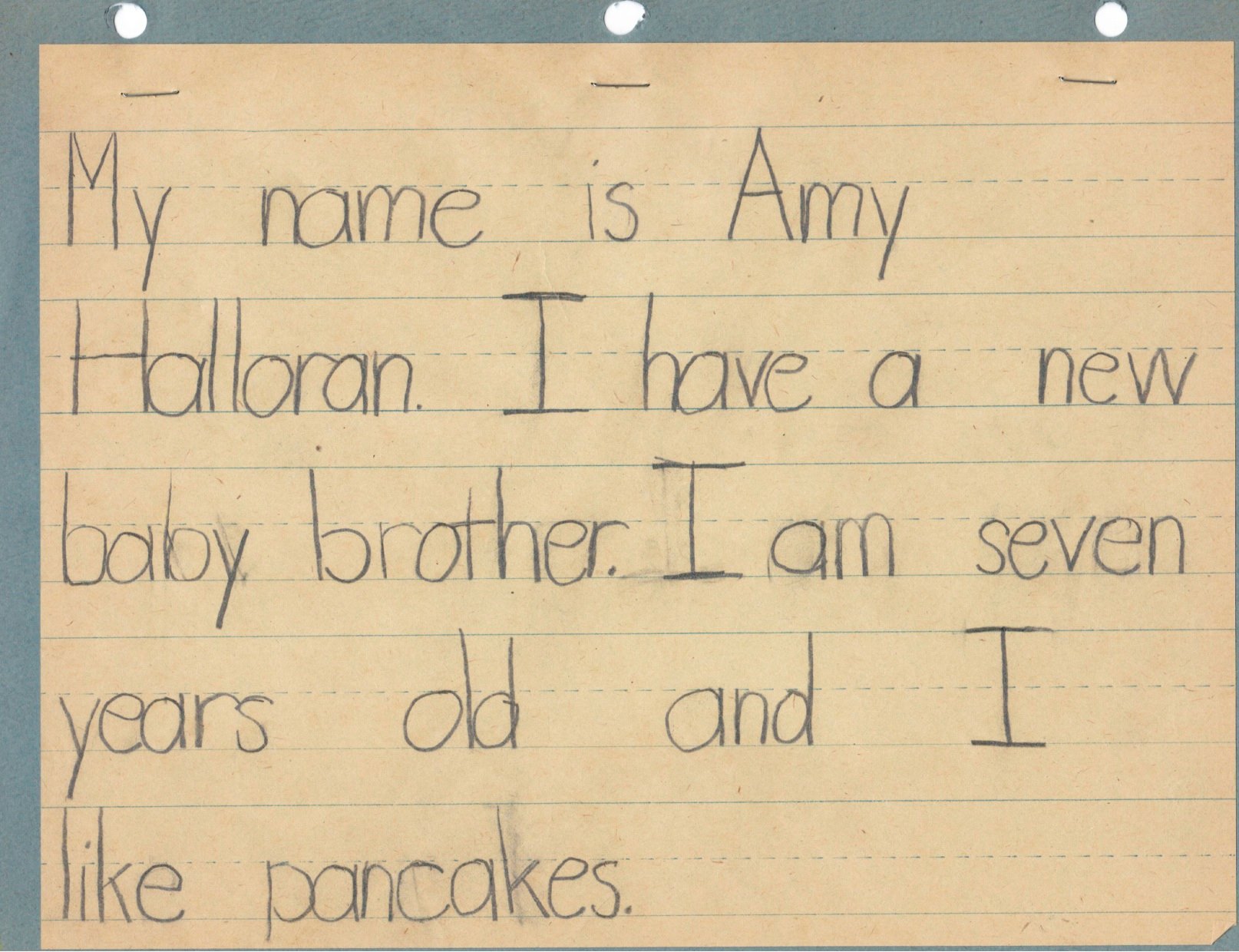

Food activist Amy Halloran has a story to tell–many of them, in fact. When Halloran was a little girl, she learned that the easiest way to connect with her father was to tell him a story when he got home from work. “It was a super strong urge,” Halloran says. “I was always very conversational,” she continues. “It’s just the way I am. I had this incredible need to connect. My family says that when I was young I would go up to anyone and make a connection with them. If we were in the grocery store and I noticed them putting something in their cart, I’d say to them, ‘We get Sugar Pops too!'”

Food activist Amy Halloran has a story to tell–many of them, in fact. When Halloran was a little girl, she learned that the easiest way to connect with her father was to tell him a story when he got home from work. “It was a super strong urge,” Halloran says. “I was always very conversational,” she continues. “It’s just the way I am. I had this incredible need to connect. My family says that when I was young I would go up to anyone and make a connection with them. If we were in the grocery store and I noticed them putting something in their cart, I’d say to them, ‘We get Sugar Pops too!'”

It was always the people who interested her, Halloran says, even as her career took her into fine dining and foodie-ism. “I made no pretenses about it,” she says of the potentially pretentious food genres. “I wanted to tell the stories of food through people.”

Halloran’s training in fiction writing served her well as she began to write profiles, “trying to catch the details of peoples’ work that would bring readers into the farm or into the creamery.” As the stories of people responsible for food production and preparation evolved, so did Halloran’s perspective. “Along the way I got interested in how we got here,” she says, of the United States’ largely industrialized food systems. “I felt compelled to tell the stories of food — not in mouthwatering words, but in the details that most of us can’t imagine. We live removed from the realities of farming. I want to illustrate the work it takes to eat.”

A self-proclaimed “Irish Catholic Polish mutt” whose family spirit is “kneejerk underdog,” Halloran’s scrappy approach led her down a path of discovery through on-the-ground experience. “I always knew I was going to be a writer and had an interest in food,” Halloran says, “but I knew that writing was not a great moneymaker.”Instead, Halloran says, she asked herself what other jobs she might do. Her local co-op newsletter posted a Farmers Market manager position and Halloran applied, successfully.

A self-proclaimed “Irish Catholic Polish mutt” whose family spirit is “kneejerk underdog,” Halloran’s scrappy approach led her down a path of discovery through on-the-ground experience. “I always knew I was going to be a writer and had an interest in food,” Halloran says, “but I knew that writing was not a great moneymaker.”Instead, Halloran says, she asked herself what other jobs she might do. Her local co-op newsletter posted a Farmers Market manager position and Halloran applied, successfully.

“That job really set my compass,” Halloran says. “It really made me see that I knew nothing about food production. It was this amazing revelation–all the prejudices I’d been given growing up in the USA, like ‘farmers are dumb,’ even though the farm kids were sitting right beside me in Honors Math class.” The job “laid out the greater job of discovery that I had to do,” she says. “I felt like I had to make amends. I was working for these farmers and I didn’t know anything about food systems. I realized that I was the dumb one in this game.”

Halloran gave up the Farmers Market position after three years to raise her children, but she never stopped telling the story of food. “How does change in food systems happen?” she asks persistently. Unwilling to subscribe to the tidy theory that “everything in food went wrong after World War II,” Halloran notes that “we don’t look backwards to the many ways that factories began to be applied to agriculture.” Halloran says she wants to “get up and close to our food systems, to take any given moment and frame it in historical context.”

One silver lining of the global pandemic, Halloran acknowledges, may be that consumers will form new habits. Early in the pandemic, store shelves were void of flour, and social media posts were rife with the home baking that was rampant in what seemed to be every American kitchen. “It’s been amazing to watch,” Halloran says. “Years ago I asked, ‘how are we giving away so much ability to cook for and feed ourselves?'”

One silver lining of the global pandemic, Halloran acknowledges, may be that consumers will form new habits. Early in the pandemic, store shelves were void of flour, and social media posts were rife with the home baking that was rampant in what seemed to be every American kitchen. “It’s been amazing to watch,” Halloran says. “Years ago I asked, ‘how are we giving away so much ability to cook for and feed ourselves?'”

Halloran remembers looking in 1985 King Arthur Flour catalogs and seeing mix after mix. “For years that’s been the market category,” she says. “People thought baking was too hard.” Now, though, Halloran hopes, “people are getting comfortable with flour and baking. ‘This is something I can do once a week,'” she imagines them thinking.

For Halloran, pancakes were the gateway to cooking from scratch; she writes about her love affair with pancakes in her book about regional grain production, The New Bread Basket. “Anyone can make a pancake,” she says.

But somehow we lost touch with our ability to take the things that come from the ground and turn them into food. “We need to engage with food for the transformative thing it is,” Halloran says. “We need to get people back into understanding agriculture and how food systems work.” Halloran advocates for regional processing facilities so that “farmers can have direct access to consumers in their communities or bio-regions.”

But somehow we lost touch with our ability to take the things that come from the ground and turn them into food. “We need to engage with food for the transformative thing it is,” Halloran says. “We need to get people back into understanding agriculture and how food systems work.” Halloran advocates for regional processing facilities so that “farmers can have direct access to consumers in their communities or bio-regions.”

We need more middle men, Halloran argues: “distributors who are focusing on local food.” If we “give farmers the ability to sell into local markets at reasonable prices,” she says, “we have a transformative capacity to heal soil, create jobs in communities, engage with food, and get people back into agriculture and food processing.” If we moved food systems closer to communities, it would go a long way “toward renewing care for the earth and for each other,” she contends.

“I feel like [the pandemic] is opening up the raw underbelly of our food systems,” Halloran says. “There’s so much opportunity for change.”

Halloran suggests that the only way for us to “get over the despair of the pandemic is to believe that we are going to have to create change.” Progressive change happens through conversation, she says. “Conversation is an accelerant of change.”

Halloran suggests that the only way for us to “get over the despair of the pandemic is to believe that we are going to have to create change.” Progressive change happens through conversation, she says. “Conversation is an accelerant of change.”

If we put health at the forefront instead of economics, Halloran continues, “we could effect change from field to food bank, with everyone at the table, with good wages and good health.”

Halloran’s activism in food systems and local grain movements takes several forms. She writes: LETTERS TO A YOUNG FARMER, THE NEW FOOD ECONOMY, and CIVIL EATS.

She teaches writing classes at farming and food conferences, “focusing on marketing for farms and food enterprises,” as well as teaching at the Troy Public Library and other community sites, often weaving together history and personal experiences. She also teaches whole grain and sourdough baking classes, helping familiarize people with stone ground flours for quick breads, griddle cakes, and everyday loaves. And Halloran runs a community meals program and food pantry at Unity House, a human services agency. “We collect and redistribute groceries from America’s over-productive food system, and make meals to share in our dining room,” she says. “While my writing and cooking may seem very different, I think they share the problem that we don’t value food and feeding, farming and the environment. I want to change that, through conversations and stories.”

Creating sweeping change may seem daunting to the average person, but Halloran offers simple suggestions for becoming more engaged with food systems. Predictably, her first suggestion involves pancakes. “It’s the lowest bar,” she says. “Make pancakes with local flour. Everyone can make a pancake, right? Just find some local flour and make pancakes. Local flour will become more and more accessible as demand grows and people access their local channels for grains.” If making pancakes fully from scratch is daunting, try a local blend like Bluebird Grain Farms’ Organic Emmer Pancake & Waffle Mix.

Creating sweeping change may seem daunting to the average person, but Halloran offers simple suggestions for becoming more engaged with food systems. Predictably, her first suggestion involves pancakes. “It’s the lowest bar,” she says. “Make pancakes with local flour. Everyone can make a pancake, right? Just find some local flour and make pancakes. Local flour will become more and more accessible as demand grows and people access their local channels for grains.” If making pancakes fully from scratch is daunting, try a local blend like Bluebird Grain Farms’ Organic Emmer Pancake & Waffle Mix.

Halloran calls grain mills “levers that farmers need to get new grains in the ground,” noting that at the turn of the 20th century, every small town had a mill, whereas currently there are only 169 USDA certified mills in the USA. “When consumers support small mills, they are participating in a revolutionary model for farmers.”

“Get a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) if you can afford it,” Halloran offers as another suggestion. “If you can’t do that, when you buy an apple at the grocery store, try to learn where it came from.” Is it a regional Honey Crisp or Jonagold? Or is it a Fuji from Japan? “Get curious about one food type,” Halloran says. “Learn how that food gets from the field to us. Challenge yourself with your food literacy.”

Halloran offers two other suggestions for those interested in increasing their food literacy:

- Check out Soul Fire Farm as a leader in the work of ending racism and injustice in food systems. “Following them is an incredible education,” Halloran says.

- Follow Ricardo Salvador of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Salvador “works with citizens, scientists, economists, and politicians to transition our current food system into one that grows healthy foods while employing sustainable and socially equitable practices.” Salvador makes complex food systems considerations accessible to laypeople, with podcast episodes like “The Broccoli Backstory” and “Science Advocacy,” which stresses the importance of evidence-based research in U.S. food policy.

To learn more about Amy Halloran and her mission to improve food systems, visit Civil Eats and Amy Halloran. And don’t miss Amy stalking the perfect pancake!

To learn more about Amy Halloran and her mission to improve food systems, visit Civil Eats and Amy Halloran. And don’t miss Amy stalking the perfect pancake!