by Ashley Lodato

Bluebird Grain Farms staff writer

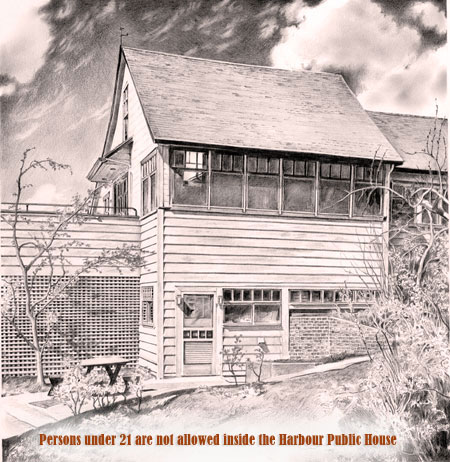

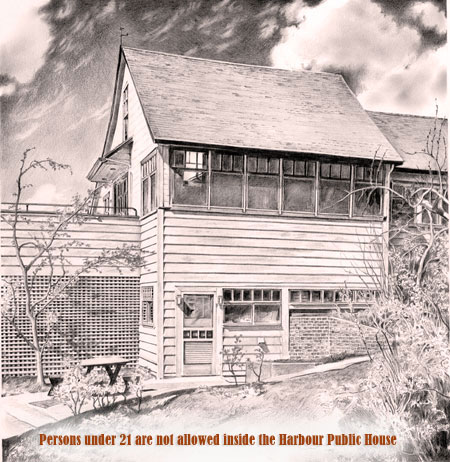

When Jim and Judy Evans, Bainbridge Island residents since the late 1960s, decided to develop a pub on a waterfront piece of property on the island’s north shore, they had two distinct objectives. Jim, who was born and raised in England, “envisioned an English-style pub as a community gathering spot without TVs and jukeboxes like their American counterparts–a place for lively dialogue fueled by the small but growing craft beer industry of the time,” says Harbour Public House general manager Jeff Waite. Meanwhile, Judy imagined a friendly pub that welcomed and served women, regardless of whether they were in the company of men. After all, in 1985 when Jim and Judy began planning the new pub, Washington State had only very recently abolished a law that prohibited unescorted women from being served while standing at a bar. Ultimately, the Evanses sought to nurture and maintain community through “heritage and hospitality.”

Harbour Public House‘s ethic of hospitality is a legacy of Jim and Judy, who built Harbour Marina–a 45-slip pleasure craft moorage facility–in 1982. The boating community that emerged from marina residents living aboard vessels was a collegial one, cultivated by Jim, a college professor, and Judy, a primary school teacher. Opening parts of their own on-site home to marina residents and friends, the Evanses encouraged gatherings, reading and board games in their day room, and offered yard space for communal gardening.

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building.

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building.

Although local residents soon warmed to the pub, initially they were wary of a new drinking establishment in the neighborhood. Says Waite, “The hard-drinking, seafaring past with a nearby bar named the “Bloody Bucket” was not yet a distant memory.” The pub opened as a non-smoking, 21+ only tavern and has remained that way ever since. Neither Jim nor Judy had any experience in the bar or restaurant industry, but they had a knack for creating community and confidence in their two adult children, who had been part of the construction and completion of the pub and who slowly assumed its managerial duties. When Jim and Judy eventually retired, their daughter Jocelyn held the reins.

Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well.

Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well.

Along with Jocelyn and Jeff Waite, Chef Jeff McClelland of the Culinary Institute of America embraced a local and regional ethic for the pub’s kitchen. “Long before ‘farm to table’ even had a name,” says Waite, “Chef Jeff has been working to shorten our delivery miles as much as possible. During that time, we have established relationships with local farmers and local producers that have enriched our lives and experiences along the way. The kitchen manager’s interaction used to be a weekly dialogue with two major food delivery distributors. Today, over 40 farmers, producers and suppliers call on him. It has changed all of our jobs quite significantly.” Later, Waite says, as price points improved, pub management applied the local and regional ethic to its wine and spirits offerings.

With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from Bluebird Grain Farms’ Organic Emmer-Farro. While diners are used to seeing such high-quality products on fine dining menus,” Waite says, “it once was very rare, and still is today for casual restaurants to take up the challenge as extensively as this.”

With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from Bluebird Grain Farms’ Organic Emmer-Farro. While diners are used to seeing such high-quality products on fine dining menus,” Waite says, “it once was very rare, and still is today for casual restaurants to take up the challenge as extensively as this.”

This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully.

This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully.

Jim and Judy phased out of the family business in 2006 and for nearly a decade, Jocelyn and Waite owned and ran the pub together. In 2015, however, Jocelyn began teaching at an island Waldorf school, while Waite remained the General Manager of both the pub and the marina operations and grounds. Despite these larger managerial roles, Waite still prioritizes giving line-item attention to the menu, in collaboration with Chef Jeff. Most recently, the Jeffs have turned their focus to wheat. Both were disappointed with most American varieties of wheat, blaming it for increasing levels of inflammation in their joints; in fact, both had been avoiding American wheat in their personal diets.

After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s Einkorn in his bread baking. He liked the results, and convinced Pane D’Amore, which provides the pub with all of its bread and buns, to develop a custom 100% Einkorn bun just for Harbour Public House, which hit diners’ plates in the summer of 2019. Later, Pane D’Amore added 5% wheat back into the bun to help with consistency. “It’s a work in progress,” Waite says.

After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s Einkorn in his bread baking. He liked the results, and convinced Pane D’Amore, which provides the pub with all of its bread and buns, to develop a custom 100% Einkorn bun just for Harbour Public House, which hit diners’ plates in the summer of 2019. Later, Pane D’Amore added 5% wheat back into the bun to help with consistency. “It’s a work in progress,” Waite says.

Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

To learn more about the Harbour Public House, visit their website.

Working in the culinary scene, Sandidge says she was attracted to “the fast paced environment, the drive to create new and exciting dishes and the feedback from customers,” adding, “You work hard to create beautiful and unique dishes, when the customers love it, it is such a great feeling.”

Working in the culinary scene, Sandidge says she was attracted to “the fast paced environment, the drive to create new and exciting dishes and the feedback from customers,” adding, “You work hard to create beautiful and unique dishes, when the customers love it, it is such a great feeling.”

Sandidge’s food blog, A Red Spatula, is strikingly appealing. Crisp and colorful photos, the textures inherent in baked grains, negative space, echoing pops of color. “I am and have always been drawn to art,” Sandidge says. “I love the use of color in particular, I assume this came from my years as a quilter.” Although she doesn’t remember being particularly artistic as a child, Sandidge says she has “worked hard to learn techniques that help me to express myself in whatever medium I am interested in at the time.”

Sandidge’s food blog, A Red Spatula, is strikingly appealing. Crisp and colorful photos, the textures inherent in baked grains, negative space, echoing pops of color. “I am and have always been drawn to art,” Sandidge says. “I love the use of color in particular, I assume this came from my years as a quilter.” Although she doesn’t remember being particularly artistic as a child, Sandidge says she has “worked hard to learn techniques that help me to express myself in whatever medium I am interested in at the time.” Before she discovered

Before she discovered  During the coronavirus pandemic, everyone seems to be baking, as evidenced by bare flour sections in grocery store aisle. For Sandidge, it’s business as usual, and she didn’t have to worry about sourcing ingredients. “One thing our family didn’t really worry about during this pandemic was food shortages,” she says. “I have always tried to make it a practice to have a well-stocked pantry. Most everything the stores were short on, I already had in good supply.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, everyone seems to be baking, as evidenced by bare flour sections in grocery store aisle. For Sandidge, it’s business as usual, and she didn’t have to worry about sourcing ingredients. “One thing our family didn’t really worry about during this pandemic was food shortages,” she says. “I have always tried to make it a practice to have a well-stocked pantry. Most everything the stores were short on, I already had in good supply.”

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building.

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building. Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well.

Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well. With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from

With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from  This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully.

This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully. After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s

After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s  Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

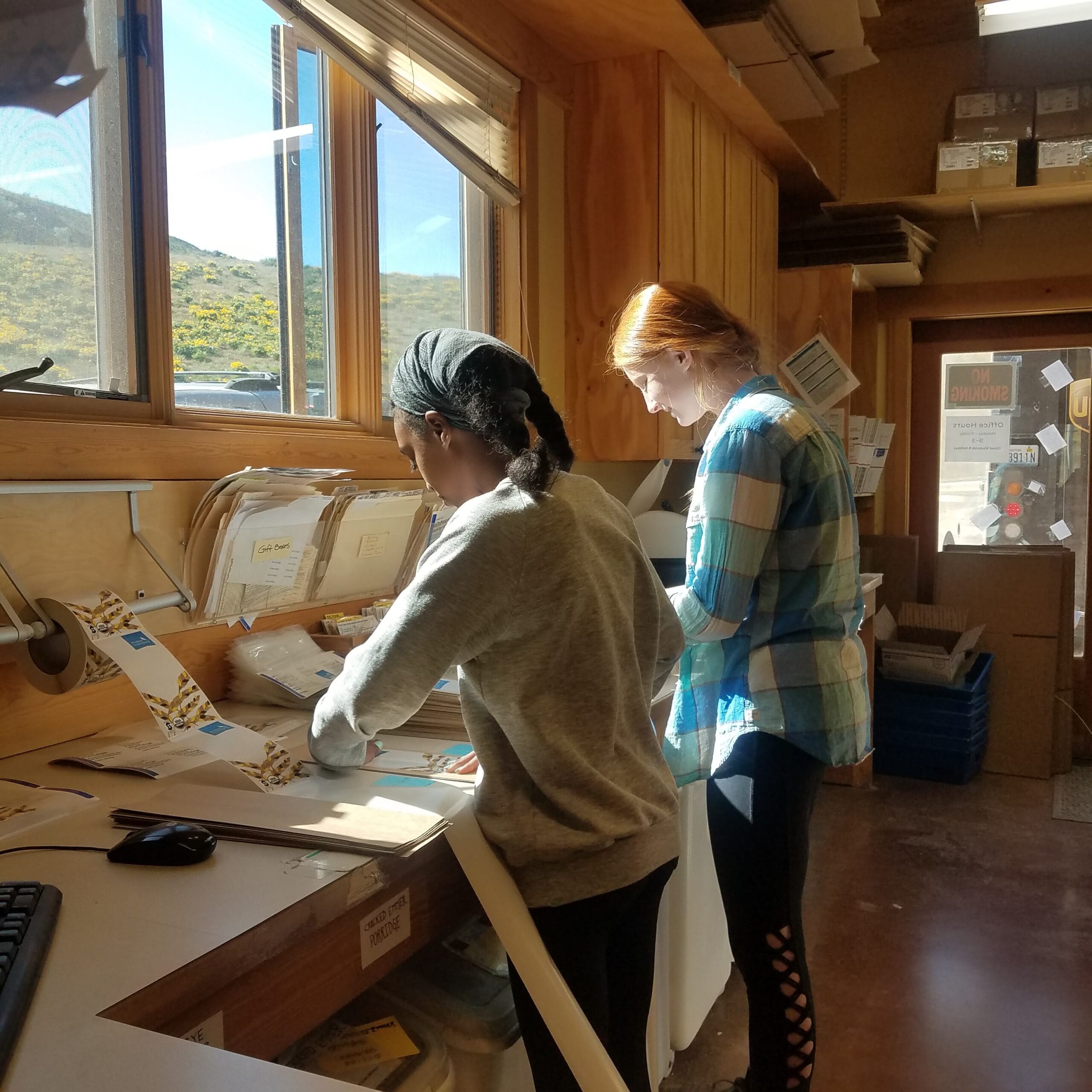

We would like to introduce our new Operations Manager, Easton Brannon. Easton started working for us at the end of January. We are grateful for Easton’s organizational skills, team spirit, and the ability to identify and solve problems quickly. She is a wonderful addition to our team.

We would like to introduce our new Operations Manager, Easton Brannon. Easton started working for us at the end of January. We are grateful for Easton’s organizational skills, team spirit, and the ability to identify and solve problems quickly. She is a wonderful addition to our team.

We are delighted to introduce our new operations manager Easton Branam. Easton joins us with extensive experience as senior-level facilities planner. She brings expertise in workflow optimization and systems planning. Easton is a military veteran and has worked as a communications officer in the army coordinating complex logistics with military teams. Easton has been at Bluebird for a month now and we feel so grateful to have such a highly qualified person join our team.

We are delighted to introduce our new operations manager Easton Branam. Easton joins us with extensive experience as senior-level facilities planner. She brings expertise in workflow optimization and systems planning. Easton is a military veteran and has worked as a communications officer in the army coordinating complex logistics with military teams. Easton has been at Bluebird for a month now and we feel so grateful to have such a highly qualified person join our team. Team C got 2nd place in the “family category” at the Ski to Sun Relay and Marathon sponsored by Methow Trails early this February. Sam, Brooke, and Bluebird’s packaging coordinator Casey Kutz skied the course in just over 2 hours. We meant to call ourselves “Team Bluebird” but auto-fill had a different plan and spit out…… c. Needless to say, we had fun and particularly enjoyed seeing farmer Sam in his lycra onesie.

Team C got 2nd place in the “family category” at the Ski to Sun Relay and Marathon sponsored by Methow Trails early this February. Sam, Brooke, and Bluebird’s packaging coordinator Casey Kutz skied the course in just over 2 hours. We meant to call ourselves “Team Bluebird” but auto-fill had a different plan and spit out…… c. Needless to say, we had fun and particularly enjoyed seeing farmer Sam in his lycra onesie. As of December 2019, all of our Bluebird Grain Farm products are certified Kosher. The kosher certification was prompted at the request of our Jewish customers. And we are glad to finally get the certification, many thanks to a USDA Value-Added Grant. If you purchase our prepackaged items you will not see the certification stamp on the bag anytime soon- all of our bags were pre-printed a year ago and it will take us some time to make this transition. Rest assured, all products are certified Kosher as of December 2019.

As of December 2019, all of our Bluebird Grain Farm products are certified Kosher. The kosher certification was prompted at the request of our Jewish customers. And we are glad to finally get the certification, many thanks to a USDA Value-Added Grant. If you purchase our prepackaged items you will not see the certification stamp on the bag anytime soon- all of our bags were pre-printed a year ago and it will take us some time to make this transition. Rest assured, all products are certified Kosher as of December 2019.

Marlene’s interest in whole grains, natural sweeteners, and abundant fresh produce soon extended beyond the family dinner table, however, when Marlene purchased a tiny health food store in Federal Way in 1976, later naming it

Marlene’s interest in whole grains, natural sweeteners, and abundant fresh produce soon extended beyond the family dinner table, however, when Marlene purchased a tiny health food store in Federal Way in 1976, later naming it

With

With  Ultimately, what Marlene’s Market & Deli has supported for two generations is a healthy lifestyle through products that promote positive and beneficial choices for the things we put into and onto our bodies. What began around Marlene’s kitchen table as a sustainable approach to living has blossomed into a community resource that is the foundation of a healthy way of life for thousands of individuals and families in southern Puget Sound.

Ultimately, what Marlene’s Market & Deli has supported for two generations is a healthy lifestyle through products that promote positive and beneficial choices for the things we put into and onto our bodies. What began around Marlene’s kitchen table as a sustainable approach to living has blossomed into a community resource that is the foundation of a healthy way of life for thousands of individuals and families in southern Puget Sound.