Ashley Lodato, Bluebird Grain Farms Staff Writer. Photos courtesy of Guerra’s Gourmet

In the 1980s, Lino Guerra noticed something. Everyone, it seemed, was suddenly interested in peppers. At the time, Lino was farming with his father in the Yakima Valley, growing peppers alongside tomatoes, peas, onions, and other produce. In response to demand for peppers, Lino, along with his wife, Hilda, slowly grew the farm to 30 acres, planting a large variety of them that he sold to restaurants and at farmers markets locally as well as in Seattle and the Tri-Cities areas. They were also busy raising their four young sons: Aaron, Chris, Geraldo, and Fabian. All the while, Lino maintained his day job as a senior chemical technician at the nearby Hanford nuclear facility because, as he says, “Farming is not an easy way to make a living.”

“We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the Guerra’s Signature Seasoning Mix. “It was just peppers and sea salt, no preservatives or fillers. We kept experimenting to find the right combination, using jalapeño, habanero, serrano, Anaheim, and about 30 other pepper varieties. We wanted to bring something different to people.”

“We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the Guerra’s Signature Seasoning Mix. “It was just peppers and sea salt, no preservatives or fillers. We kept experimenting to find the right combination, using jalapeño, habanero, serrano, Anaheim, and about 30 other pepper varieties. We wanted to bring something different to people.”

In 2002, Lino says, “Everything changed.” Hilda and Geraldo were involved in a serious car accident. “It pushed everything to a stop,” Lino says. “We had to change gears.”

The two oldest boys, Aaron and Chris, helped their grandfather, Antonio, continue farming. “When they eventually went to college,” Lino says, “that farming experience was useful. It gave them the gift of a work ethic. It taught them about the value of a family business. It made them what they are now: responsible, creative, outgoing.”

All four boys went on to college, learning skills in marketing, culinary arts, and management. After finishing culinary school, Chris cooked at a downtown Seattle restaurant before leaving to work full-time with Guerras Gourmet Catering. “We had always offered the catering,” says Chris, “but we didn’t really advertise it. It started as a way for my parents to offer some of the fresh vegetables from the farm as ready-to-eat meals at the farmer’s markets so that we didn’t have to take any produce home with us.”

In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites.

In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites.

Fajitas were the Guerras’ specialty, as well as the Guerra boys’ original training in preparing food for others to enjoy. “My dad taught all four of us to make fajitas,” Chris says. “Over time, we each developed our own methods. Now we compete for who makes the best fajita.”

The same Guerra-friendly competition applies to salsa, Chris says. “Aaron is known as the one who can make the hottest salsa. I like a little flair, so I make mine different, like using orange tomatoes or fruit. Geraldo is more sophisticated because he did cooking school at an art institute. His is a medium-range salsa that is very refined. Fabian, the youngest, takes a little bit from all three of us to make his own unique salsa.”

“We each have our own stir-fries, too,” Chris adds. “And it all comes from my mom and dad going to the market and cooking up fajitas.”

Working for Guerra’s Gourmet Catering, Chris says, is a different experience than working in a restaurant. Although restaurants now have widely adopted a “farm to table” philosophy, it was less common back when Chris made the leap from Seattle fine dining to Yakima Valley catering. For a farm family, however, it came naturally. “When you live on a farm you get to be creative with seasonal vegetables all the time. In the spring we would cook asparagus in a stir fry, then we’d have jicama and radishes; we’d use onions and tomatoes when they came into season, bell peppers, corn. We had the opportunity to design our meals around what was ready to harvest.”

Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to Bluebird Grain Farms. “We were already using vegetables from our own and other local farms, and we were sourcing cheese locally from our neighbor, Daniel’s Artisan, so what about the pizza dough was going to make it unique and better?” asks Chris. “As a chef, you’re not satisfied until each ingredient is right.”

Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to Bluebird Grain Farms. “We were already using vegetables from our own and other local farms, and we were sourcing cheese locally from our neighbor, Daniel’s Artisan, so what about the pizza dough was going to make it unique and better?” asks Chris. “As a chef, you’re not satisfied until each ingredient is right.”

“We chose Bluebird because it’s easy to work with, but it’s unlike any other whole wheat flour,” Chris continues. “You can feel the texture. The taste is different. There’s nothing else like it.”

“We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic Emmer, Einka, and Dark Northern Rye all have unique flavors by themselves. Then there’s the Methow Hard Red and Pasayten Hard White wheat flours that help keep everything together. Each one has its own characteristics, body, and flavor. They taste great. They allow us to create a pizza crust not readily available anywhere else.”

“We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic Emmer, Einka, and Dark Northern Rye all have unique flavors by themselves. Then there’s the Methow Hard Red and Pasayten Hard White wheat flours that help keep everything together. Each one has its own characteristics, body, and flavor. They taste great. They allow us to create a pizza crust not readily available anywhere else.”

From pizza, wood-fired bread were a natural segue for the Guerras. “When we first got the flours and started making breads,” says Chris, “all we were doing was burning up bread. I tried to tell everyone, ‘I’m not a baker, I’m a chef!’ But my dad told me that if you’re a cook, the experience is built in your heart. Eventually, we figured out our systems.”

The Guerras’ bread systems are so figured out, in fact, that they are able to ship loaves to Hawaii, where an uncle sells them at island farmer’s markets. “We ship the loaves wrapped in paper bags inside the boxes,” says Chris. “They take a couple of days to arrive, and they apparently still taste perfectly fresh when they get there.”

The bread, pizza crusts, English muffins, and rolls that come out of that oven are “so satisfying,” Chris says. “It’s so wholesome, it’s delicious, and you’re not just consuming empty calories.” Equally important, Chris believes, is that “you’re eating flour that has a story. We like the story behind each ingredient. Our cheese has a story, our vegetables have a story, our grains have a story. We spend time and effort to learn the stories of the products we’re serving.”

A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.”

A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.”

As farmers and owners of a small family business, buying locally has long been a priority for the Guerras, but it hasn’t always been easy. While the well-drained soil and hot, dry climate of the Yakima Valley are ideal for growing peppers, they’re not as conducive to root crops. “We need to buy our beets and carrots from farms in other regions,” Chris says. “It takes a lot of time to go to this farm for this ingredient, then to a different farm for that ingredient. But one of the things you learn in culinary school–not to mention just understanding it intuitively from growing up eating your own garden produce–is how important fresh vegetables are.”

Early in the days of the catering venture, sourcing vegetables was challenging. “Everything was getting shipped off to Seattle markets,” Chris says. “It took years to develop the relationships we now have with these area farmers. I am very thankful they recognize me from when I was younger, going with my dad to visit them. I just had to learn to get in line earlier for our vegetables.”

Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the Guerra’s Box: a nearly ready-to-go charcuterie board, with a Fuego cheese from Daniel’s Artisan, a loaf of Bluebird wood-fired bread, a bottle of Guerra’s Signature Seasoning, dried Italian mushrooms, Mt. Adams Honey from Zillah, and various cured meats from Glondo’s Sausage Company in Cle Elum. “It’s comfort food,” Chris says.

Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the Guerra’s Box: a nearly ready-to-go charcuterie board, with a Fuego cheese from Daniel’s Artisan, a loaf of Bluebird wood-fired bread, a bottle of Guerra’s Signature Seasoning, dried Italian mushrooms, Mt. Adams Honey from Zillah, and various cured meats from Glondo’s Sausage Company in Cle Elum. “It’s comfort food,” Chris says.

A silver lining of the pandemic for Hilda and Lino is having all four boys involved in the farm, spice, and catering business: Chris and Geraldo on a full-time basis, Aaron and Fabian as time allows. The pandemic has also allowed the Guerras to focus on their seasonings; they’ve since created an extra spicy blend for those who like a bit more heat or an “extra kick.”

The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

Listening to the ideas, one gets the idea that if he had time, Chris could simply rattle off recommendations for using the spice mix all day long. But the thing is, the ideas all bear out; the seasoning blend is delicious in all of the suggested applications.

Rather than introducing competing flavors to what might seem like incongruous pairings–hot peppers and stone fruits, for example–the spice mix draws out the sweetness of the fruit by providing contrast. The Guerras intuitively understand how the seasoning plays a supporting role, allowing the main focus to remain on the pizza crust, the pasta sauce, or the salad blend. Once again, Lino Guerra proves correct: if you’re a cook, the experience is built in your heart.

Click the following links to learn more about Guerra’s Gourmet products, and Guerra’s Gourmet Catering or visit them on Facebook.

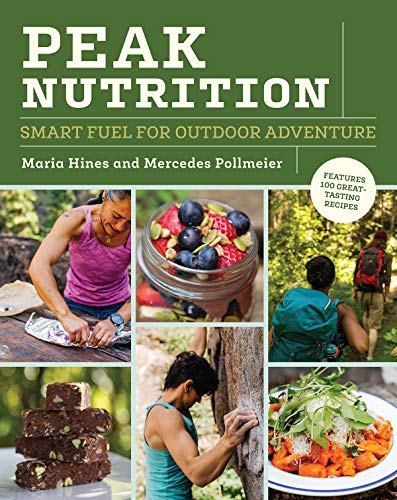

A 2020 National Outdoor Book Award winner, Peak Nutrition was born of necessity, says Hines. “In all these years, I’ve yet to come across a comprehensive nutritional cookbook that is dedicated to mountain sports. Professional and recreational mountain athletes require proper nutrition to fuel their bodies, minds, and spirits. This book is for outdoor athletes who want to perform at their best.”

A 2020 National Outdoor Book Award winner, Peak Nutrition was born of necessity, says Hines. “In all these years, I’ve yet to come across a comprehensive nutritional cookbook that is dedicated to mountain sports. Professional and recreational mountain athletes require proper nutrition to fuel their bodies, minds, and spirits. This book is for outdoor athletes who want to perform at their best.”

The Methow Valley was also where Hines discovered Bluebird Grain Farms and its products, through a connection with Chef John Sundstrom, owner and chef at Seattle’s Lark Restaurant. “Chef John introduced me to Bluebird Grain Farms and I’ve been using the products for 16 years now,” Hines says. “My fave is making farro risotto!” She uses, of course, Bluebird Grain Farms’ Organic Whole Grain Emmer Farro.

The Methow Valley was also where Hines discovered Bluebird Grain Farms and its products, through a connection with Chef John Sundstrom, owner and chef at Seattle’s Lark Restaurant. “Chef John introduced me to Bluebird Grain Farms and I’ve been using the products for 16 years now,” Hines says. “My fave is making farro risotto!” She uses, of course, Bluebird Grain Farms’ Organic Whole Grain Emmer Farro.

“We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the

“We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the  In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites.

In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites. Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to

Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to  “We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic

“We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic  A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.”

A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.” Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the

Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the  The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

Kiritz and his partner in business and in life, Katie Ryan, have traveled and worked extensively throughout the United States in various aspects of food production and preparation. Ryan, a chef and the culinary talent behind Wild Spoon Kitchen, has a dedication to whole, natural ingredients that began with her mother’s cooking and “developed over a lifetime of cooking, gardening, and connecting more with her natural landscapes.” Says Kiritz, “Her commitment to local and seasonal-based cooking, and keeping a homestead kitchen (rich with her own set of fermentation and preservation projects) makes our collaboration natural and deeper, and solidifies my own motivation to bake in this same way.”

Kiritz and his partner in business and in life, Katie Ryan, have traveled and worked extensively throughout the United States in various aspects of food production and preparation. Ryan, a chef and the culinary talent behind Wild Spoon Kitchen, has a dedication to whole, natural ingredients that began with her mother’s cooking and “developed over a lifetime of cooking, gardening, and connecting more with her natural landscapes.” Says Kiritz, “Her commitment to local and seasonal-based cooking, and keeping a homestead kitchen (rich with her own set of fermentation and preservation projects) makes our collaboration natural and deeper, and solidifies my own motivation to bake in this same way.”

For Kiritz and Ryan, contributing to the solution means offering a sliding scale to their customers. “Our food systems have been structured to make access to quality, local, healthful, environmentally regenerative foods inequitable,” Kiritz says. “If paying the offered price would make it harder for our customers to meet other basic needs, we’ll sell our products at a lower price, no questions asked.”

For Kiritz and Ryan, contributing to the solution means offering a sliding scale to their customers. “Our food systems have been structured to make access to quality, local, healthful, environmentally regenerative foods inequitable,” Kiritz says. “If paying the offered price would make it harder for our customers to meet other basic needs, we’ll sell our products at a lower price, no questions asked.” Kiritz and Ryan’s dream is to have “our own land and teaching space, to offer mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities, host retreats, and offer up the use of our space free of charge for organizations representing [marginalized] communities.” Kiritz acknowledges that realizing this dream may be some time away, but says “we’re committed to some version of this down the road.” Even without this land and space, though, Rising Grain Project and Wild Spoon Kitchen offer opportunities to learn, through classes and the Wild Spoon Cooking School, as well as through embracing the chance to connect people through food. It is this exercise–the mindful practice of breaking bread with others–that Kiritz and Ryan seek to nurture within their community. “As I’ve continued to explore my relationship with baking bread and cooking in general,” Kiritz says, “I’ve discovered that I most love…how a simple, traditional craft can bring people together and create moments of joy and connection.”

Kiritz and Ryan’s dream is to have “our own land and teaching space, to offer mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities, host retreats, and offer up the use of our space free of charge for organizations representing [marginalized] communities.” Kiritz acknowledges that realizing this dream may be some time away, but says “we’re committed to some version of this down the road.” Even without this land and space, though, Rising Grain Project and Wild Spoon Kitchen offer opportunities to learn, through classes and the Wild Spoon Cooking School, as well as through embracing the chance to connect people through food. It is this exercise–the mindful practice of breaking bread with others–that Kiritz and Ryan seek to nurture within their community. “As I’ve continued to explore my relationship with baking bread and cooking in general,” Kiritz says, “I’ve discovered that I most love…how a simple, traditional craft can bring people together and create moments of joy and connection.”