Ashley Lodato, Bluebird Grain Farms staff writer.

Those who know Portland, OR’s Wellspent Market owner Jim Dixon, those who have heard him expound upon the virtues of really good olive oil, may be surprised to learn that for a time in his life, he bought his olive oil at Costco. “I considered myself a well-informed cook at the time,” Dixon says, “but I had never tasted good olive oil.”

In the mid-1990s, however, Dixon’s life–or at least his palate–changed. Dixon and his wife, a “New Jersey Sicilian American,” traveled to Italy, where Dixon had his first taste of delicious, bona-fide extra-virgin (a term that is unregulated in the US) olive oil. There was no going back. “After that,” Dixon says, “we went back every couple of years to support our own habits. All I ever wanted was an endless supply of good olive oil.”

The couple brought home as much good olive oil as they could each trip, but after a few trips it wasn’t sustainable. “We could get enough oil home to last until the next time,” Dixon says. “So in 1999 we were traveling along the Amalfi Coast, and stopped at this great little farm-to-table place–before farm-to-table was a thing–and they made their own olive oil. We cut a deal on shipping and decided to start importing.”

The couple brought home as much good olive oil as they could each trip, but after a few trips it wasn’t sustainable. “We could get enough oil home to last until the next time,” Dixon says. “So in 1999 we were traveling along the Amalfi Coast, and stopped at this great little farm-to-table place–before farm-to-table was a thing–and they made their own olive oil. We cut a deal on shipping and decided to start importing.”

“We knew nothing about importing,” Dixon continues. “We’d ship a large quantity, sell half of it to friends to cover the shipping cost, and keep the rest for our own kitchen.”

Real Good Food , Dixon’s original import company, was founded on a mission of supplying his own pantry, but soon became a source of high quality Italian food products for others in the Portland area. Dixon came from a technical writing background and was thus connected with various Portland restaurant owners, including Genoa (now closed) and Nostrana, both of which, along with others, started buying his imported oil. Dixon soon added to his imports salt and farro, a grain with a nutty flavor and ancient roots and a staple of Italian cooking.

, Dixon’s original import company, was founded on a mission of supplying his own pantry, but soon became a source of high quality Italian food products for others in the Portland area. Dixon came from a technical writing background and was thus connected with various Portland restaurant owners, including Genoa (now closed) and Nostrana, both of which, along with others, started buying his imported oil. Dixon soon added to his imports salt and farro, a grain with a nutty flavor and ancient roots and a staple of Italian cooking.

Dixon’s interest in farro led him to his ongoing relationship with Bluebird Grain Farms. “Brooke [Lucy, Bluebird co-owner] came down here in a pickup with all these 50-lb bags of farro and flour,” Dixon says. “We’d buy it and put it in small packages.” Farro’s whole-grain, nutritious profile appealed to Dixon’s sensibilities, and he likes to support small family agriculture, so Bluebird was a fit for him. “And then suddenly farro got popular and was sold everywhere,” he says.

When Dixon decided to open a storefront, he says it was very simple. “We didn’t have enough inventory, so we were spreading product out and filling the empty shelves with art and other things.” Dixon’s business partner recognized that there were other things the market could offer, so they started expanding. Eventually Wellspent Market began carrying “pantry staples from around the world,” ranging from vinegar to grains to beans to dairy to housewares to wines (which are managed by Dixon’s son, Joe), and everything in between. It’s “everything we love, nothing we don’t,” Dixon says.

When Dixon decided to open a storefront, he says it was very simple. “We didn’t have enough inventory, so we were spreading product out and filling the empty shelves with art and other things.” Dixon’s business partner recognized that there were other things the market could offer, so they started expanding. Eventually Wellspent Market began carrying “pantry staples from around the world,” ranging from vinegar to grains to beans to dairy to housewares to wines (which are managed by Dixon’s son, Joe), and everything in between. It’s “everything we love, nothing we don’t,” Dixon says.

“We’re always on the lookout for small, local producers,” says Dixon. “We seek out women-owned producers, other marginalized producers.” The way Dixon sees it, he and his business partner, Noah Cable, are “a couple of privileged white guys who have a platform.” So through their sourcing decisions for Wellspent Market, they’re leveraging their influence.

For years, Dixon was a member of Slow Food Portland, which promotes “good, clean, fair food.” That mantra guides Dixon–“it’s what we do at Wellspent,” he says. “We’re about real food, clean food. And that means no chemicals, but also food produced without a giant environmental impact. Fair food–food that doesn’t exploit the people who grow and harvest it.”

Also for years—20 of them—Dixon’s operation was a one-man show. “I picked up pallets of olive oil in my old Vanagon, filled and labeled bottles, and made deliveries. I was the bookkeeper, recipe developer, and janitor, and I worked a day job [as a technical writer for the City of Portland]. As my long-time customers remember, the Real Good Food ‘store’ was only open a couple of days each week, and they had to wait if they needed oil or salt.” With the addition of Cable, Dixon was able to expand his offerings and focus on his passion: real food, good food.

Also for years—20 of them—Dixon’s operation was a one-man show. “I picked up pallets of olive oil in my old Vanagon, filled and labeled bottles, and made deliveries. I was the bookkeeper, recipe developer, and janitor, and I worked a day job [as a technical writer for the City of Portland]. As my long-time customers remember, the Real Good Food ‘store’ was only open a couple of days each week, and they had to wait if they needed oil or salt.” With the addition of Cable, Dixon was able to expand his offerings and focus on his passion: real food, good food.

Through Wellspent Market, Dixon likes to “tell stories through food.” He refers to the Culinary Breeding Network and talks about “working with growers to develop products that grow in the region.” Pointing to Feast Portland — which celebrates the diverse food and beverage communities in Portland — Dixon notes that he learns about food producers from other farmers and growers. “Stories taste good,” Dixon says. “All these small food networks are sharing each others’ stories. We tell the stories about the food we sell. And our customers respond to that.”

“There’s a lot of cool agricultural stuff going on around here,” Dixon says. “Bluebird Grain Farms fits into that for us.”

“There’s a lot of cool agricultural stuff going on around here,” Dixon says. “Bluebird Grain Farms fits into that for us.”

Real Good Food and Wellspent Market are inextricably linked, but in simple terms Real Good Food is the brand and the regional wholesale business, while Wellspent Market is the retail food store. Like other retail shops, Wellspent Market had to reframe its practices for COVID. Prior to the pandemic, about half of Wellspent Market’s sales were restaurant purchases. “All that revenue went away,” says Dixon. “We closed our store doors and wondered, ‘Are we doomed?'”

Dixon and Cable took the opportunity to ramp up the online sales system they had been developing slowly, and focused on responding to individual customer demand. “When things shut down, we had to figure out how to get products to our customers,” Dixon says. “We did deliveries, we did curbside pickup. We made it work. But it also gave us the incentive to fine tune our online ordering systems.”

“We increased our revenue. We’re still not making a lot of money, but at least we didn’t go out of business,” Dixon acknowledges cheerfully.

“We increased our revenue. We’re still not making a lot of money, but at least we didn’t go out of business,” Dixon acknowledges cheerfully.

Gazing at the hundreds (thousands?) of products on Wellspent Market’s shelves, or scrolling through them on the market’s website, the apparent complexity can be overwhelming. “Do I want the organic gold sesame paste or the organic white sesame paste? Zinfandel vinegar or rosé vinegar?” you wonder. But there’s a method to the multitude of products. “Our overarching goal is to sell good food that helps people eat better,” Dixon says. “There are some products that will make your life better. Good olive oil is one of them. If you can understand how a few simple ingredients will make your life better, you’ll enjoy your food more. Our goal is just to tell you how to make food good.” To this end, Wellspent Market offers a vast archive of simple, tasty recipes.

“I can cook, but I’m not a chef,” Dixon notes. “I like simple food–food with humble ingredients. I like to encourage people to cook this way. I think this can help people cook more at home and eat better.”

Dixon keeps his pantry stocked with good olive oil and salts, sources of acid like vinegars and lemons, and focuses on simple proteins and grains. “Most of my diet is beans, grains, and the cabbage family,” Dixon says. “I like whole grain pasta, different flavored pastas, Bluebird’s Einka & French Lentil Blend.”

Dixon keeps his pantry stocked with good olive oil and salts, sources of acid like vinegars and lemons, and focuses on simple proteins and grains. “Most of my diet is beans, grains, and the cabbage family,” Dixon says. “I like whole grain pasta, different flavored pastas, Bluebird’s Einka & French Lentil Blend.”

Yes, he eats carbs, and plenty of them, heedless of the bum rap carbohydrates get in mainstream media. “I get cranky when people push me about that,” Dixon sighs. “People don’t pay attention to the details, they just hear something is bad and eliminate it. Gluten intolerance is more related to the industrial food system. Those ancient grains [like Bluebird’s Einka and Emmer Farro, for example] are much better, they digest better. Their makeup is just so different than the highly processed grains you typically see on shelves.” (There’s not much at Wellspent Market that Dixon doesn’t like to eat, but gluten-free pasta tops that list.)

Dixon credit’s Wellspent Market’s “fierce loyal customer base” with the store’s sustainability. Customers rely on the shop’s newsletter with new recipes, the shelves stocked with a comfortable blend of old favorites and new products. A customer or a restaurant chef might ask about a particular product the store doesn’t sell, and Dixon’s team investigates it and decides whether to stock it.

Dixon credit’s Wellspent Market’s “fierce loyal customer base” with the store’s sustainability. Customers rely on the shop’s newsletter with new recipes, the shelves stocked with a comfortable blend of old favorites and new products. A customer or a restaurant chef might ask about a particular product the store doesn’t sell, and Dixon’s team investigates it and decides whether to stock it.

“Over the years the only change is that now we offer more stuff. We like to play around with different flavor profiles, experiment with different products. But our customers know they can count on us to offer their reliable pantry preferences,” Dixon says. “Ultimately, we’re still focused on real food, on good food–on real good food.”

Read Dixon’s olive oil “rant” HERE.

Learn more about Wellspent Market HERE or find them on Facebook.

It was this spirit of exploration that led Kraemer to

It was this spirit of exploration that led Kraemer to

When COVID hit, just 18 months into the Kraemers’ ownership of Caso’s, the store was challenged less by supply issues than by transportation complications. Sure, Caso’s had to sell toilet paper by the roll just like all the other stores, as panicked buyers scooped up excessive supplies of the newly commodified item. But in terms of stocking the store with fresh produce and staples, the Kraemers had to figure out how to get food from farms to their shelves and bins. “We didn’t lack for items that we could pick up ourselves,” Kraemer says. “When we couldn’t get things from a supplier we reached out directly to farms. It got crazy there for a while. My husband was making weekly runs to the Basin to buy potatoes and beans.”

When COVID hit, just 18 months into the Kraemers’ ownership of Caso’s, the store was challenged less by supply issues than by transportation complications. Sure, Caso’s had to sell toilet paper by the roll just like all the other stores, as panicked buyers scooped up excessive supplies of the newly commodified item. But in terms of stocking the store with fresh produce and staples, the Kraemers had to figure out how to get food from farms to their shelves and bins. “We didn’t lack for items that we could pick up ourselves,” Kraemer says. “When we couldn’t get things from a supplier we reached out directly to farms. It got crazy there for a while. My husband was making weekly runs to the Basin to buy potatoes and beans.” Kraemer emphasizes the value she places on workplace safety, not just following OSHA guidelines, but creating a healthy and inclusive work environment. “We are dedicated to the customers and to our team,” she says. “It’s extremely important to us. We are committed to the health and wellness of our community at all different levels because it’s all connected. We feel like if we create a positive and inclusive work environment for our team, it’s going to make the customer experience even better too.”

Kraemer emphasizes the value she places on workplace safety, not just following OSHA guidelines, but creating a healthy and inclusive work environment. “We are dedicated to the customers and to our team,” she says. “It’s extremely important to us. We are committed to the health and wellness of our community at all different levels because it’s all connected. We feel like if we create a positive and inclusive work environment for our team, it’s going to make the customer experience even better too.” Kraemer’s path to becoming a retail grocery store owner/operator was somewhat unconventional, with her previous professional background in insurance, sales, marketing, and rental properties, as well as some business ventures she and Clark have undertaken together over the years.

Kraemer’s path to becoming a retail grocery store owner/operator was somewhat unconventional, with her previous professional background in insurance, sales, marketing, and rental properties, as well as some business ventures she and Clark have undertaken together over the years. A 2020 National Outdoor Book Award winner, Peak Nutrition was born of necessity, says Hines. “In all these years, I’ve yet to come across a comprehensive nutritional cookbook that is dedicated to mountain sports. Professional and recreational mountain athletes require proper nutrition to fuel their bodies, minds, and spirits. This book is for outdoor athletes who want to perform at their best.”

A 2020 National Outdoor Book Award winner, Peak Nutrition was born of necessity, says Hines. “In all these years, I’ve yet to come across a comprehensive nutritional cookbook that is dedicated to mountain sports. Professional and recreational mountain athletes require proper nutrition to fuel their bodies, minds, and spirits. This book is for outdoor athletes who want to perform at their best.”

The Methow Valley was also where Hines discovered

The Methow Valley was also where Hines discovered  “We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the

“We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the  In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites.

In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites. Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to

Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to  “We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic

“We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic  A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.”

A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.” Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the

Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the  The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

Kiritz and his partner in business and in life, Katie Ryan, have traveled and worked extensively throughout the United States in various aspects of food production and preparation. Ryan, a chef and the culinary talent behind Wild Spoon Kitchen, has a dedication to whole, natural ingredients that began with her mother’s cooking and “developed over a lifetime of cooking, gardening, and connecting more with her natural landscapes.” Says Kiritz, “Her commitment to local and seasonal-based cooking, and keeping a homestead kitchen (rich with her own set of fermentation and preservation projects) makes our collaboration natural and deeper, and solidifies my own motivation to bake in this same way.”

Kiritz and his partner in business and in life, Katie Ryan, have traveled and worked extensively throughout the United States in various aspects of food production and preparation. Ryan, a chef and the culinary talent behind Wild Spoon Kitchen, has a dedication to whole, natural ingredients that began with her mother’s cooking and “developed over a lifetime of cooking, gardening, and connecting more with her natural landscapes.” Says Kiritz, “Her commitment to local and seasonal-based cooking, and keeping a homestead kitchen (rich with her own set of fermentation and preservation projects) makes our collaboration natural and deeper, and solidifies my own motivation to bake in this same way.”

For Kiritz and Ryan, contributing to the solution means offering a sliding scale to their customers. “Our food systems have been structured to make access to quality, local, healthful, environmentally regenerative foods inequitable,” Kiritz says. “If paying the offered price would make it harder for our customers to meet other basic needs, we’ll sell our products at a lower price, no questions asked.”

For Kiritz and Ryan, contributing to the solution means offering a sliding scale to their customers. “Our food systems have been structured to make access to quality, local, healthful, environmentally regenerative foods inequitable,” Kiritz says. “If paying the offered price would make it harder for our customers to meet other basic needs, we’ll sell our products at a lower price, no questions asked.” Kiritz and Ryan’s dream is to have “our own land and teaching space, to offer mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities, host retreats, and offer up the use of our space free of charge for organizations representing [marginalized] communities.” Kiritz acknowledges that realizing this dream may be some time away, but says “we’re committed to some version of this down the road.” Even without this land and space, though, Rising Grain Project and Wild Spoon Kitchen offer opportunities to learn, through classes and the Wild Spoon Cooking School, as well as through embracing the chance to connect people through food. It is this exercise–the mindful practice of breaking bread with others–that Kiritz and Ryan seek to nurture within their community. “As I’ve continued to explore my relationship with baking bread and cooking in general,” Kiritz says, “I’ve discovered that I most love…how a simple, traditional craft can bring people together and create moments of joy and connection.”

Kiritz and Ryan’s dream is to have “our own land and teaching space, to offer mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities, host retreats, and offer up the use of our space free of charge for organizations representing [marginalized] communities.” Kiritz acknowledges that realizing this dream may be some time away, but says “we’re committed to some version of this down the road.” Even without this land and space, though, Rising Grain Project and Wild Spoon Kitchen offer opportunities to learn, through classes and the Wild Spoon Cooking School, as well as through embracing the chance to connect people through food. It is this exercise–the mindful practice of breaking bread with others–that Kiritz and Ryan seek to nurture within their community. “As I’ve continued to explore my relationship with baking bread and cooking in general,” Kiritz says, “I’ve discovered that I most love…how a simple, traditional craft can bring people together and create moments of joy and connection.”

Food activist

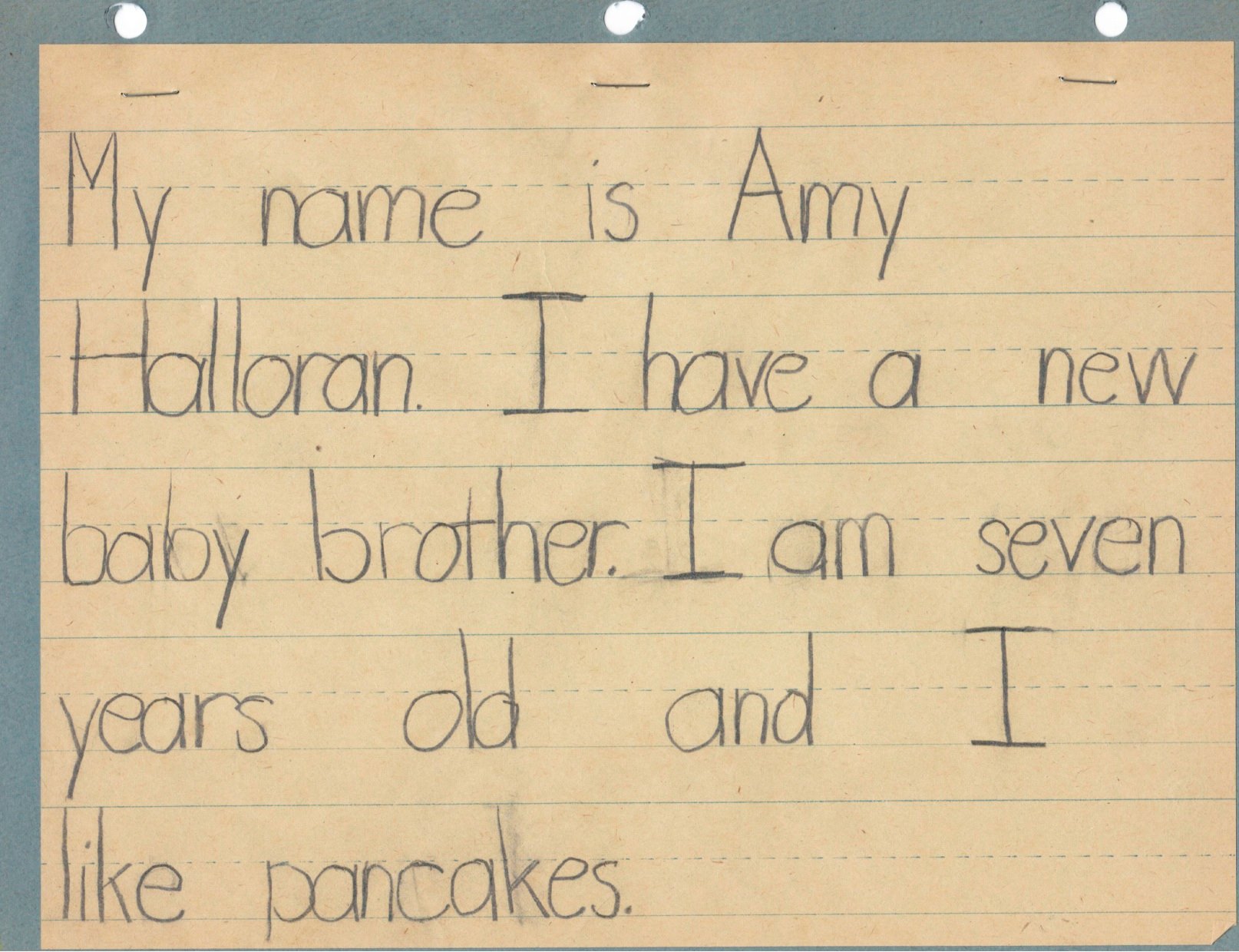

Food activist  A self-proclaimed “Irish Catholic Polish mutt” whose family spirit is “kneejerk underdog,” Halloran’s scrappy approach led her down a path of discovery through on-the-ground experience. “I always knew I was going to be a writer and had an interest in food,” Halloran says, “but I knew that writing was not a great moneymaker.”Instead, Halloran says, she asked herself what other jobs she might do. Her local co-op newsletter posted a Farmers Market manager position and Halloran applied, successfully.

A self-proclaimed “Irish Catholic Polish mutt” whose family spirit is “kneejerk underdog,” Halloran’s scrappy approach led her down a path of discovery through on-the-ground experience. “I always knew I was going to be a writer and had an interest in food,” Halloran says, “but I knew that writing was not a great moneymaker.”Instead, Halloran says, she asked herself what other jobs she might do. Her local co-op newsletter posted a Farmers Market manager position and Halloran applied, successfully. One silver lining of the global pandemic, Halloran acknowledges, may be that consumers will form new habits. Early in the pandemic, store shelves were void of flour, and social media posts were rife with the home baking that was rampant in what seemed to be every American kitchen. “It’s been amazing to watch,” Halloran says. “Years ago I asked, ‘how are we giving away so much ability to cook for and feed ourselves?'”

One silver lining of the global pandemic, Halloran acknowledges, may be that consumers will form new habits. Early in the pandemic, store shelves were void of flour, and social media posts were rife with the home baking that was rampant in what seemed to be every American kitchen. “It’s been amazing to watch,” Halloran says. “Years ago I asked, ‘how are we giving away so much ability to cook for and feed ourselves?'” But somehow we lost touch with our ability to take the things that come from the ground and turn them into food. “We need to engage with food for the transformative thing it is,” Halloran says. “We need to get people back into understanding agriculture and how food systems work.” Halloran advocates for regional processing facilities so that “farmers can have direct access to consumers in their communities or bio-regions.”

But somehow we lost touch with our ability to take the things that come from the ground and turn them into food. “We need to engage with food for the transformative thing it is,” Halloran says. “We need to get people back into understanding agriculture and how food systems work.” Halloran advocates for regional processing facilities so that “farmers can have direct access to consumers in their communities or bio-regions.” Halloran suggests that the only way for us to “get over the despair of the pandemic is to believe that we are going to have to create change.” Progressive change happens through conversation, she says. “Conversation is an accelerant of change.”

Halloran suggests that the only way for us to “get over the despair of the pandemic is to believe that we are going to have to create change.” Progressive change happens through conversation, she says. “Conversation is an accelerant of change.” Creating sweeping change may seem daunting to the average person, but Halloran offers simple suggestions for becoming more engaged with food systems. Predictably, her first suggestion involves pancakes. “It’s the lowest bar,” she says. “Make pancakes with

Creating sweeping change may seem daunting to the average person, but Halloran offers simple suggestions for becoming more engaged with food systems. Predictably, her first suggestion involves pancakes. “It’s the lowest bar,” she says. “Make pancakes with  To learn more about Amy Halloran and her mission to improve food systems, visit

To learn more about Amy Halloran and her mission to improve food systems, visit  Working in the culinary scene, Sandidge says she was attracted to “the fast paced environment, the drive to create new and exciting dishes and the feedback from customers,” adding, “You work hard to create beautiful and unique dishes, when the customers love it, it is such a great feeling.”

Working in the culinary scene, Sandidge says she was attracted to “the fast paced environment, the drive to create new and exciting dishes and the feedback from customers,” adding, “You work hard to create beautiful and unique dishes, when the customers love it, it is such a great feeling.”

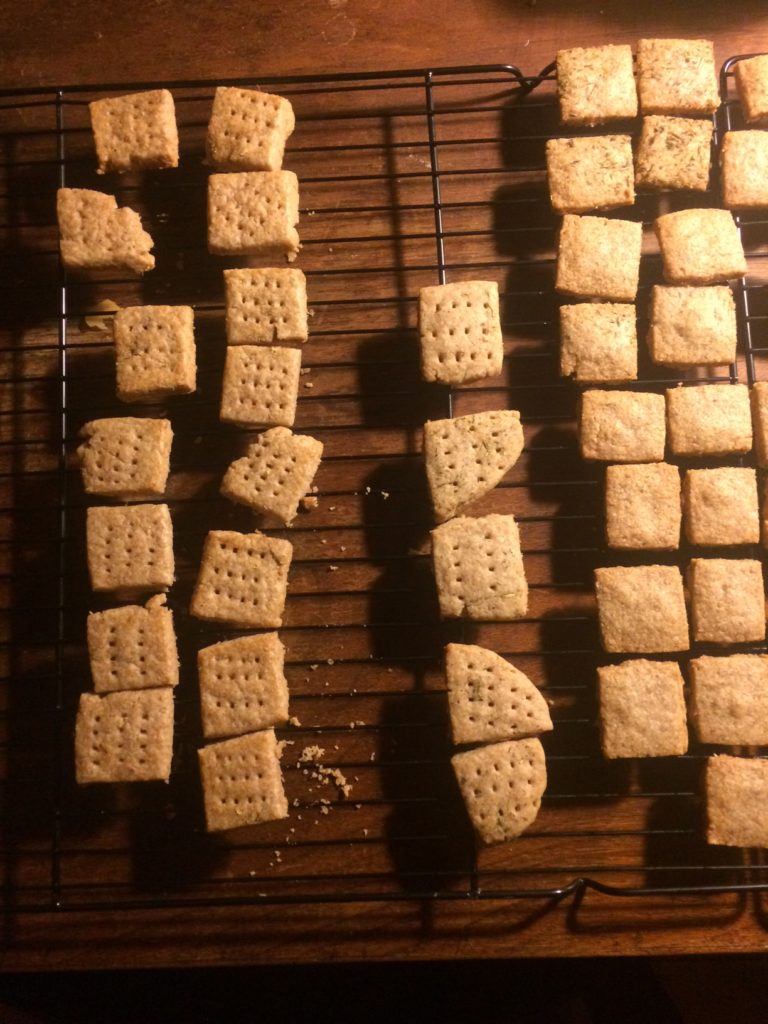

Sandidge’s food blog, A Red Spatula, is strikingly appealing. Crisp and colorful photos, the textures inherent in baked grains, negative space, echoing pops of color. “I am and have always been drawn to art,” Sandidge says. “I love the use of color in particular, I assume this came from my years as a quilter.” Although she doesn’t remember being particularly artistic as a child, Sandidge says she has “worked hard to learn techniques that help me to express myself in whatever medium I am interested in at the time.”

Sandidge’s food blog, A Red Spatula, is strikingly appealing. Crisp and colorful photos, the textures inherent in baked grains, negative space, echoing pops of color. “I am and have always been drawn to art,” Sandidge says. “I love the use of color in particular, I assume this came from my years as a quilter.” Although she doesn’t remember being particularly artistic as a child, Sandidge says she has “worked hard to learn techniques that help me to express myself in whatever medium I am interested in at the time.” Before she discovered

Before she discovered  During the coronavirus pandemic, everyone seems to be baking, as evidenced by bare flour sections in grocery store aisle. For Sandidge, it’s business as usual, and she didn’t have to worry about sourcing ingredients. “One thing our family didn’t really worry about during this pandemic was food shortages,” she says. “I have always tried to make it a practice to have a well-stocked pantry. Most everything the stores were short on, I already had in good supply.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, everyone seems to be baking, as evidenced by bare flour sections in grocery store aisle. For Sandidge, it’s business as usual, and she didn’t have to worry about sourcing ingredients. “One thing our family didn’t really worry about during this pandemic was food shortages,” she says. “I have always tried to make it a practice to have a well-stocked pantry. Most everything the stores were short on, I already had in good supply.”

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building.

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building. Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well.

Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well. With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from

With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from  This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully.

This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully. After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s

After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s  Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

Marlene’s interest in whole grains, natural sweeteners, and abundant fresh produce soon extended beyond the family dinner table, however, when Marlene purchased a tiny health food store in Federal Way in 1976, later naming it

Marlene’s interest in whole grains, natural sweeteners, and abundant fresh produce soon extended beyond the family dinner table, however, when Marlene purchased a tiny health food store in Federal Way in 1976, later naming it

With

With  Ultimately, what Marlene’s Market & Deli has supported for two generations is a healthy lifestyle through products that promote positive and beneficial choices for the things we put into and onto our bodies. What began around Marlene’s kitchen table as a sustainable approach to living has blossomed into a community resource that is the foundation of a healthy way of life for thousands of individuals and families in southern Puget Sound.

Ultimately, what Marlene’s Market & Deli has supported for two generations is a healthy lifestyle through products that promote positive and beneficial choices for the things we put into and onto our bodies. What began around Marlene’s kitchen table as a sustainable approach to living has blossomed into a community resource that is the foundation of a healthy way of life for thousands of individuals and families in southern Puget Sound.