As a girl who grew up on orchards and later went on to fruit sales, Stephanie Kraemer knows her fruit. “Apples, cherries, and pears–that was my whole world before buying a grocery store,” Kraemer says. Kraemer, who with her husband, Clark, purchased Caso’s Country Foods in Okanogan, WA, just two and a half years ago, was raised on Oroville orchards and developed her appreciation for fresh produce early. “Dad was a grower and an orchardist,” she says. “I know the importance of fresh fruits and vegetables to a healthy diet. I also value quality, since I always had access to great produce.”

Working in fruit sales for 18 years–10 of them in international fruit sales–Kraemer says that she has a great appreciation of all that goes into growing, harvesting, and shipping produce, to stock grocery stores in response to customer demand. The exacting standards she had for the quality of the fruit she shipped while in sales carried over to her role in buying for Caso’s Country Foods. “I’m quite critical of the quality of what we carry,” she says.

Working in fruit sales for 18 years–10 of them in international fruit sales–Kraemer says that she has a great appreciation of all that goes into growing, harvesting, and shipping produce, to stock grocery stores in response to customer demand. The exacting standards she had for the quality of the fruit she shipped while in sales carried over to her role in buying for Caso’s Country Foods. “I’m quite critical of the quality of what we carry,” she says.

Her commitment to high-quality produce as well as her dedication to the Okanogan region drives Kraemer’s buying strategy; she sources local and regional produce and other products whenever possible. In fact, Kraemer’s decision to seek out local products was made simultaneously with her decision to buy the store. “Immediately my brain said ‘I want this whole section of things from the Okanogan area,'” she said. “So I’m constantly trying to find local artisans and growers, to discover fresh things.”

It was this spirit of exploration that led Kraemer to Bluebird Grain Farms. “I was up in Winthrop at the Rocking Horse Bakery,” she says, “and I learned about Bluebird’s products. I knew I needed to reach out and learn more about them. When I saw how passionate Bluebird is about supplying nutritious products that are grown locally and produced sustainably–well, it was just all the things that I loved.” As she does with any new product she tests in the store, Kraemer went broad with her first Bluebird order. “I started with everything,” she says. “I didn’t know what customers would want. So far it’s going quite well.”

It was this spirit of exploration that led Kraemer to Bluebird Grain Farms. “I was up in Winthrop at the Rocking Horse Bakery,” she says, “and I learned about Bluebird’s products. I knew I needed to reach out and learn more about them. When I saw how passionate Bluebird is about supplying nutritious products that are grown locally and produced sustainably–well, it was just all the things that I loved.” As she does with any new product she tests in the store, Kraemer went broad with her first Bluebird order. “I started with everything,” she says. “I didn’t know what customers would want. So far it’s going quite well.”

Kraemer says that although she and Clark are relatively new to retail grocery work, they’re backed by a solid team of employees. “We’re learning from them,” Kraemer says. “The core team stayed on. They’ve been unbelievably helpful to us as we learn the business. We so appreciate their support. I don’t know how we would be doing this without them.” For the Kraemers, walking into an industry that they had no experience in was “quite the learning curve,” Kraemer says. “But it’s fun to learn something new.”

“It caught our adult daughter a bit off guard when we bought the business though,” she adds. “She was off having her own adventures and thought we were stable in our careers. And then suddenly here we were, navigating the unknown.”

Kraemer relies on both her team’s recommendations and her sense of adventure to guide her purchases. “I get excited about offering new and different things,” she says. “I like to cook and I’ve traveled quite a both personally and for my previous job in fruit sales. I know there are so many flavors and foods out there that are so delicious, as well as healthy and nutritious. It thrills me to offer these flavors to others.” Although Clark isn’t involved in the daily operations of the store, Kraemer says that he’s a cook with an adventuresome palate, which influences some of her decisions about the products Caso’s stocks.

As far as predicting what products will be big hits with her Okanogan customers, Kraemer says “It’s a bit of trial and error. I keep making investments in offering things in our valley that might not be offered elsewhere.” She adds, “My real passion in the store is watching other businesses succeed and grow, and I can help them do that by carrying and promoting their products.” She mentions some of the area growers and producers she favors along with Bluebird: Be Well juices, Coulee Farms flowers and baked goods, Cyrus Saffron, Spiceology signature spice blends. Kraemer says that part of her investment in small area businesses comes from her curiosity about “someone starting something from scratch and growing it into a success.”

When COVID hit, just 18 months into the Kraemers’ ownership of Caso’s, the store was challenged less by supply issues than by transportation complications. Sure, Caso’s had to sell toilet paper by the roll just like all the other stores, as panicked buyers scooped up excessive supplies of the newly commodified item. But in terms of stocking the store with fresh produce and staples, the Kraemers had to figure out how to get food from farms to their shelves and bins. “We didn’t lack for items that we could pick up ourselves,” Kraemer says. “When we couldn’t get things from a supplier we reached out directly to farms. It got crazy there for a while. My husband was making weekly runs to the Basin to buy potatoes and beans.”

When COVID hit, just 18 months into the Kraemers’ ownership of Caso’s, the store was challenged less by supply issues than by transportation complications. Sure, Caso’s had to sell toilet paper by the roll just like all the other stores, as panicked buyers scooped up excessive supplies of the newly commodified item. But in terms of stocking the store with fresh produce and staples, the Kraemers had to figure out how to get food from farms to their shelves and bins. “We didn’t lack for items that we could pick up ourselves,” Kraemer says. “When we couldn’t get things from a supplier we reached out directly to farms. It got crazy there for a while. My husband was making weekly runs to the Basin to buy potatoes and beans.”

Kraemer credits her staff with keeping the store open and the people–both customers and employees–safe. “It was just navigating the unknown that was the most challenging part,” she says. “As an essential business, we got all this information about what we should be doing, but it changed daily. It’s a credit to our team that we were able to stay open, stocked, and safe.”

Kraemer emphasizes the value she places on workplace safety, not just following OSHA guidelines, but creating a healthy and inclusive work environment. “We are dedicated to the customers and to our team,” she says. “It’s extremely important to us. We are committed to the health and wellness of our community at all different levels because it’s all connected. We feel like if we create a positive and inclusive work environment for our team, it’s going to make the customer experience even better too.”

Kraemer emphasizes the value she places on workplace safety, not just following OSHA guidelines, but creating a healthy and inclusive work environment. “We are dedicated to the customers and to our team,” she says. “It’s extremely important to us. We are committed to the health and wellness of our community at all different levels because it’s all connected. We feel like if we create a positive and inclusive work environment for our team, it’s going to make the customer experience even better too.”

This commitment to community is something that the Kraemers have carried over from the previous owners of Caso’s, who Kraemer says were “very involved in community, with strong support for kids and youth sports.” The Kraemers have diversified their community outreach, continuing to support youth activities but also in the Imagination Library and animals.

Ah yes, animals. “We have lots of animals,” Kraemer says. She and Clark manage a 21-cat sanctuary, and she serves on the board of OkanDogs, the Okanogan Region’s only dog rescue organization.

Kraemer’s path to becoming a retail grocery store owner/operator was somewhat unconventional, with her previous professional background in insurance, sales, marketing, and rental properties, as well as some business ventures she and Clark have undertaken together over the years.

Kraemer’s path to becoming a retail grocery store owner/operator was somewhat unconventional, with her previous professional background in insurance, sales, marketing, and rental properties, as well as some business ventures she and Clark have undertaken together over the years.

But ultimately what drew her to Caso’s is a passion for the Okanogan community.

“I’ve always lived in the Okanogan Region,” Kraemer says. “For many years I commuted to Chelan and traveled a lot for work. I was working in different communities, and I loved those communities, but they weren’t mine. Part of the big draw for us buying the business was to be more involved in our home community. This is home. This is where we wanted to be.”

For more information about Caso’s Country Foods, visit their website.

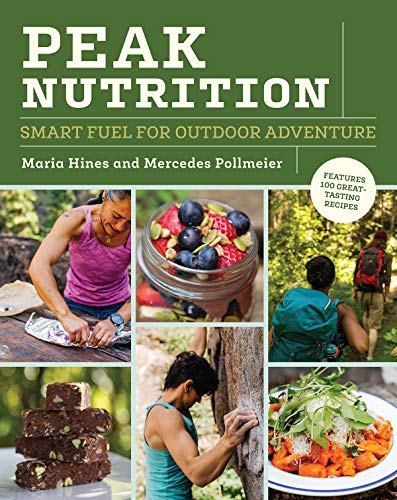

A 2020 National Outdoor Book Award winner, Peak Nutrition was born of necessity, says Hines. “In all these years, I’ve yet to come across a comprehensive nutritional cookbook that is dedicated to mountain sports. Professional and recreational mountain athletes require proper nutrition to fuel their bodies, minds, and spirits. This book is for outdoor athletes who want to perform at their best.”

A 2020 National Outdoor Book Award winner, Peak Nutrition was born of necessity, says Hines. “In all these years, I’ve yet to come across a comprehensive nutritional cookbook that is dedicated to mountain sports. Professional and recreational mountain athletes require proper nutrition to fuel their bodies, minds, and spirits. This book is for outdoor athletes who want to perform at their best.”

The Methow Valley was also where Hines discovered

The Methow Valley was also where Hines discovered  “We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the

“We were getting so many requests that we started drying the peppers and blending them into a spice mix,” Lino says of what is now the  In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites.

In considering the catering menu offerings, the Guerras turned to their favorites. Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to

Over the years, the Guerras began making wood-fired pizzas, and this culinary path led them to  “We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic

“We always say we only have one chance to wow people,” Chris explains. “So it needs to be from that first bite. Bluebird’s organic  A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.”

A consistent theme throughout Guerras’ story is the pepper. “Everything we do involves peppers,” Chris says. “From appetizers to amuse-bouche to salsa to entrees–it’s all about the pepper. I like to introduce people to different pepper varieties. If you only shop in the grocery store, you’d think that jalapeños and bell peppers are the only varieties out there.” Yakima Valley consumers are adventuresome eaters, Chris notes, and “we have a younger generation of residents who understand the importance of buying locally.” Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the

Like everyone else in the foodservice industry, the Guerras have had to adapt their business model to COVID. “The pandemic forced us to change how we do everything,” Chris says. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘How do we continue safely and provide a product to an audience that wants something local?'” The Guerras’ solution was to take one item from each of their suppliers and create the  The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

The spice blend is not, as one might assume, simply a way to add flavor and heat to fajitas or tacos. Its uses are seemingly limitless, under the imaginative culinary minds of the Guerra family. “Garnish pizza with it, or sprinkle it on focaccia or breadsticks right before you bake them,” Chris says. “Shake it up in salad dressing, top Caprese salads with it, simmer it with fresh herbs and tomatoes from the garden, and make a marinara sauce. Dust fresh peaches, nectarines, or apples with it. Put a spray of it on ice cream.”

Kiritz and his partner in business and in life, Katie Ryan, have traveled and worked extensively throughout the United States in various aspects of food production and preparation. Ryan, a chef and the culinary talent behind Wild Spoon Kitchen, has a dedication to whole, natural ingredients that began with her mother’s cooking and “developed over a lifetime of cooking, gardening, and connecting more with her natural landscapes.” Says Kiritz, “Her commitment to local and seasonal-based cooking, and keeping a homestead kitchen (rich with her own set of fermentation and preservation projects) makes our collaboration natural and deeper, and solidifies my own motivation to bake in this same way.”

Kiritz and his partner in business and in life, Katie Ryan, have traveled and worked extensively throughout the United States in various aspects of food production and preparation. Ryan, a chef and the culinary talent behind Wild Spoon Kitchen, has a dedication to whole, natural ingredients that began with her mother’s cooking and “developed over a lifetime of cooking, gardening, and connecting more with her natural landscapes.” Says Kiritz, “Her commitment to local and seasonal-based cooking, and keeping a homestead kitchen (rich with her own set of fermentation and preservation projects) makes our collaboration natural and deeper, and solidifies my own motivation to bake in this same way.”

For Kiritz and Ryan, contributing to the solution means offering a sliding scale to their customers. “Our food systems have been structured to make access to quality, local, healthful, environmentally regenerative foods inequitable,” Kiritz says. “If paying the offered price would make it harder for our customers to meet other basic needs, we’ll sell our products at a lower price, no questions asked.”

For Kiritz and Ryan, contributing to the solution means offering a sliding scale to their customers. “Our food systems have been structured to make access to quality, local, healthful, environmentally regenerative foods inequitable,” Kiritz says. “If paying the offered price would make it harder for our customers to meet other basic needs, we’ll sell our products at a lower price, no questions asked.” Kiritz and Ryan’s dream is to have “our own land and teaching space, to offer mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities, host retreats, and offer up the use of our space free of charge for organizations representing [marginalized] communities.” Kiritz acknowledges that realizing this dream may be some time away, but says “we’re committed to some version of this down the road.” Even without this land and space, though, Rising Grain Project and Wild Spoon Kitchen offer opportunities to learn, through classes and the Wild Spoon Cooking School, as well as through embracing the chance to connect people through food. It is this exercise–the mindful practice of breaking bread with others–that Kiritz and Ryan seek to nurture within their community. “As I’ve continued to explore my relationship with baking bread and cooking in general,” Kiritz says, “I’ve discovered that I most love…how a simple, traditional craft can bring people together and create moments of joy and connection.”

Kiritz and Ryan’s dream is to have “our own land and teaching space, to offer mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities, host retreats, and offer up the use of our space free of charge for organizations representing [marginalized] communities.” Kiritz acknowledges that realizing this dream may be some time away, but says “we’re committed to some version of this down the road.” Even without this land and space, though, Rising Grain Project and Wild Spoon Kitchen offer opportunities to learn, through classes and the Wild Spoon Cooking School, as well as through embracing the chance to connect people through food. It is this exercise–the mindful practice of breaking bread with others–that Kiritz and Ryan seek to nurture within their community. “As I’ve continued to explore my relationship with baking bread and cooking in general,” Kiritz says, “I’ve discovered that I most love…how a simple, traditional craft can bring people together and create moments of joy and connection.”

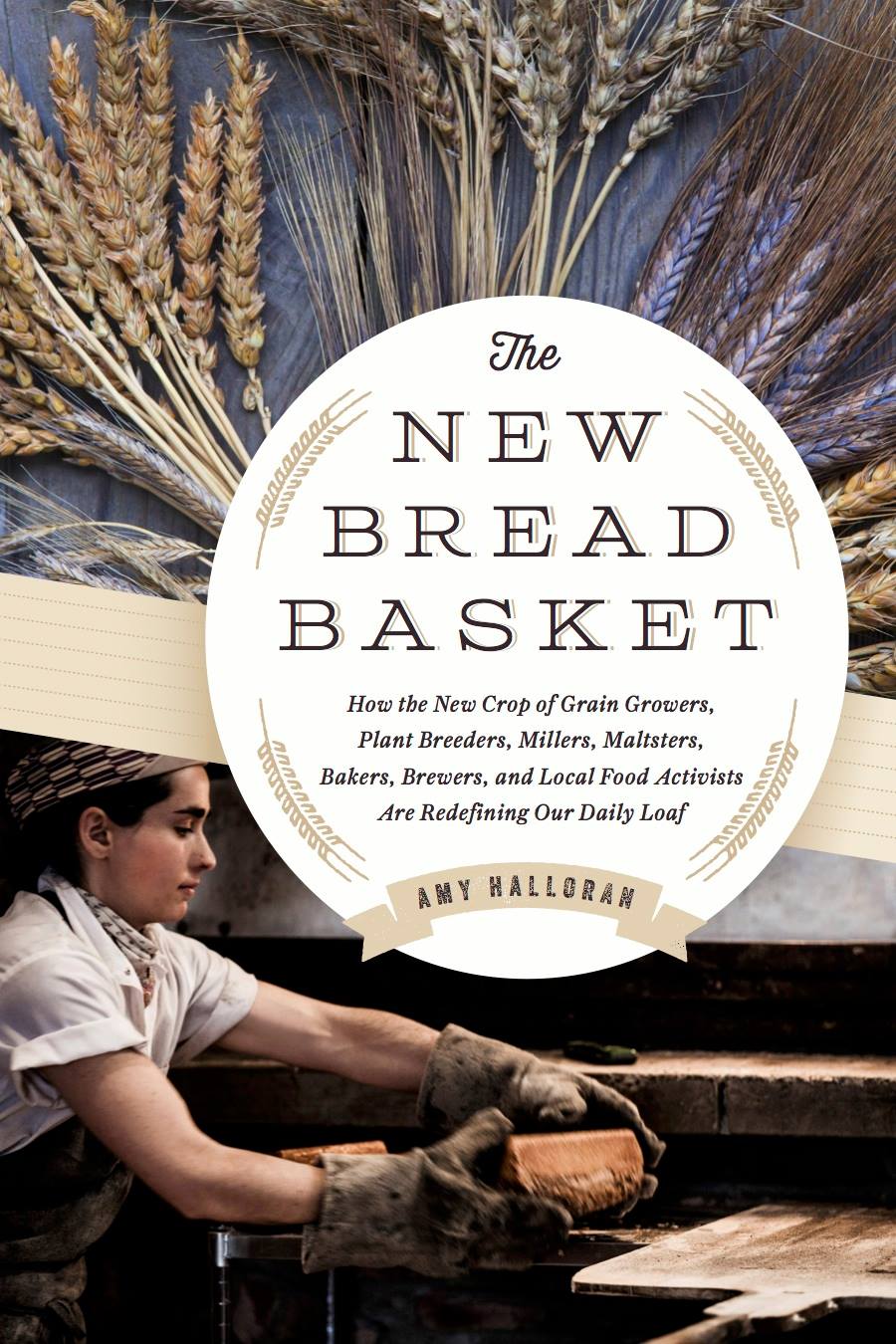

Food activist

Food activist  A self-proclaimed “Irish Catholic Polish mutt” whose family spirit is “kneejerk underdog,” Halloran’s scrappy approach led her down a path of discovery through on-the-ground experience. “I always knew I was going to be a writer and had an interest in food,” Halloran says, “but I knew that writing was not a great moneymaker.”Instead, Halloran says, she asked herself what other jobs she might do. Her local co-op newsletter posted a Farmers Market manager position and Halloran applied, successfully.

A self-proclaimed “Irish Catholic Polish mutt” whose family spirit is “kneejerk underdog,” Halloran’s scrappy approach led her down a path of discovery through on-the-ground experience. “I always knew I was going to be a writer and had an interest in food,” Halloran says, “but I knew that writing was not a great moneymaker.”Instead, Halloran says, she asked herself what other jobs she might do. Her local co-op newsletter posted a Farmers Market manager position and Halloran applied, successfully. One silver lining of the global pandemic, Halloran acknowledges, may be that consumers will form new habits. Early in the pandemic, store shelves were void of flour, and social media posts were rife with the home baking that was rampant in what seemed to be every American kitchen. “It’s been amazing to watch,” Halloran says. “Years ago I asked, ‘how are we giving away so much ability to cook for and feed ourselves?'”

One silver lining of the global pandemic, Halloran acknowledges, may be that consumers will form new habits. Early in the pandemic, store shelves were void of flour, and social media posts were rife with the home baking that was rampant in what seemed to be every American kitchen. “It’s been amazing to watch,” Halloran says. “Years ago I asked, ‘how are we giving away so much ability to cook for and feed ourselves?'” But somehow we lost touch with our ability to take the things that come from the ground and turn them into food. “We need to engage with food for the transformative thing it is,” Halloran says. “We need to get people back into understanding agriculture and how food systems work.” Halloran advocates for regional processing facilities so that “farmers can have direct access to consumers in their communities or bio-regions.”

But somehow we lost touch with our ability to take the things that come from the ground and turn them into food. “We need to engage with food for the transformative thing it is,” Halloran says. “We need to get people back into understanding agriculture and how food systems work.” Halloran advocates for regional processing facilities so that “farmers can have direct access to consumers in their communities or bio-regions.” Halloran suggests that the only way for us to “get over the despair of the pandemic is to believe that we are going to have to create change.” Progressive change happens through conversation, she says. “Conversation is an accelerant of change.”

Halloran suggests that the only way for us to “get over the despair of the pandemic is to believe that we are going to have to create change.” Progressive change happens through conversation, she says. “Conversation is an accelerant of change.” Creating sweeping change may seem daunting to the average person, but Halloran offers simple suggestions for becoming more engaged with food systems. Predictably, her first suggestion involves pancakes. “It’s the lowest bar,” she says. “Make pancakes with

Creating sweeping change may seem daunting to the average person, but Halloran offers simple suggestions for becoming more engaged with food systems. Predictably, her first suggestion involves pancakes. “It’s the lowest bar,” she says. “Make pancakes with  To learn more about Amy Halloran and her mission to improve food systems, visit

To learn more about Amy Halloran and her mission to improve food systems, visit  Working in the culinary scene, Sandidge says she was attracted to “the fast paced environment, the drive to create new and exciting dishes and the feedback from customers,” adding, “You work hard to create beautiful and unique dishes, when the customers love it, it is such a great feeling.”

Working in the culinary scene, Sandidge says she was attracted to “the fast paced environment, the drive to create new and exciting dishes and the feedback from customers,” adding, “You work hard to create beautiful and unique dishes, when the customers love it, it is such a great feeling.”

Sandidge’s food blog, A Red Spatula, is strikingly appealing. Crisp and colorful photos, the textures inherent in baked grains, negative space, echoing pops of color. “I am and have always been drawn to art,” Sandidge says. “I love the use of color in particular, I assume this came from my years as a quilter.” Although she doesn’t remember being particularly artistic as a child, Sandidge says she has “worked hard to learn techniques that help me to express myself in whatever medium I am interested in at the time.”

Sandidge’s food blog, A Red Spatula, is strikingly appealing. Crisp and colorful photos, the textures inherent in baked grains, negative space, echoing pops of color. “I am and have always been drawn to art,” Sandidge says. “I love the use of color in particular, I assume this came from my years as a quilter.” Although she doesn’t remember being particularly artistic as a child, Sandidge says she has “worked hard to learn techniques that help me to express myself in whatever medium I am interested in at the time.” Before she discovered

Before she discovered  During the coronavirus pandemic, everyone seems to be baking, as evidenced by bare flour sections in grocery store aisle. For Sandidge, it’s business as usual, and she didn’t have to worry about sourcing ingredients. “One thing our family didn’t really worry about during this pandemic was food shortages,” she says. “I have always tried to make it a practice to have a well-stocked pantry. Most everything the stores were short on, I already had in good supply.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, everyone seems to be baking, as evidenced by bare flour sections in grocery store aisle. For Sandidge, it’s business as usual, and she didn’t have to worry about sourcing ingredients. “One thing our family didn’t really worry about during this pandemic was food shortages,” she says. “I have always tried to make it a practice to have a well-stocked pantry. Most everything the stores were short on, I already had in good supply.”

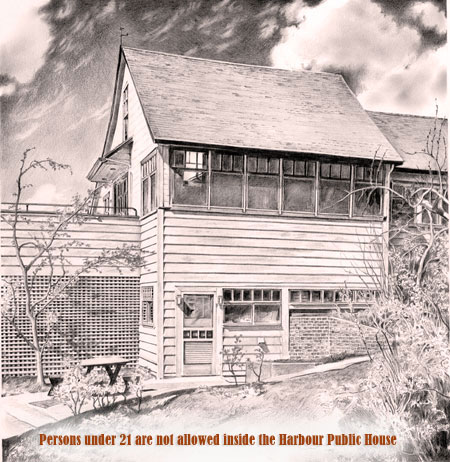

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building.

The building’s heritage is a post-Civil War story. Built by war veteran Ambrose Grow and his wife Amanda in 1881, the homestead was the site of the Grow family’s fruit and vegetable gardens and free-ranging cattle. In 1991, Jim and Judy completed a five-year construction project and opened the Harbour Public House on the footprint of the home where the Grows had homesteaded a century before, and even re-purposed some of the old-growth fir found in the walls and floors of the original building. Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well.

Jocelyn, who had scrapped law school plans in favor of joining the family enterprise, brought one of the pub’s regular patrons into the family fold, marrying Jeff Waite–now general manager–in 1994. It was Jocelyn who hired the pub’s first kitchen manager, who in turn added two enduring items to the food menu: Pacific Cod Fish & Chips, and the Pub Burger. They kept Jim Evans’ commitment to local craft beers as well. With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from

With the bounty of the Pacific Northwest at its fingertips, Harbour Public House’s menu is a cornucopia of products sourced regionally and locally. The pub buys much of its meat “on the hoof,” says Waite, and is “particularly proud of its products from a Spanaway beef ranch and a Port Townsend goat ranch.” Much of the pub’s green produce comes from an island farmer. The Puget Sound basic and the Washington coast provide cheese, clams, oysters, grains, legumes, and dairy, while the pub’s cod and tuna is Pacific-caught and humanely treated by Bainbridge resident fishermen. Farro items on the menu come from  This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully.

This commitment to quality ingredients is a bit of a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, as patrons often have difficulty understanding the relationship between food quality and prices. The market demands inexpensive food, yet increasingly customers want to eat and drink products with integrity: locally grown or sourced, organic, humane. Restaurant prices, then, reflect not only the quality of the food, but also the cost of preparing it thoughtfully. After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s

After becoming acquainted with Bluebird Grain Farms at one of the early Chef’s Collaborative F2C2 gatherings and incorporating emmer-farro into their menu, in 2019 Waite began experimenting with Bluebird’s  Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

Like the Pub Burger’s bun, some things at Harbour Public House are evolving. Others, however, remain consistent, such as the atmosphere of the pub as a welcoming spot for excellent food and beverages, a strong community, and lively conversation. To this end, Waite notes, with a nod to the pub’s roots, “No TVs or juke-boxes have ever been permanently installed and women continue to be a large percentage of its clientele.”

Marlene’s interest in whole grains, natural sweeteners, and abundant fresh produce soon extended beyond the family dinner table, however, when Marlene purchased a tiny health food store in Federal Way in 1976, later naming it

Marlene’s interest in whole grains, natural sweeteners, and abundant fresh produce soon extended beyond the family dinner table, however, when Marlene purchased a tiny health food store in Federal Way in 1976, later naming it

With

With  Ultimately, what Marlene’s Market & Deli has supported for two generations is a healthy lifestyle through products that promote positive and beneficial choices for the things we put into and onto our bodies. What began around Marlene’s kitchen table as a sustainable approach to living has blossomed into a community resource that is the foundation of a healthy way of life for thousands of individuals and families in southern Puget Sound.

Ultimately, what Marlene’s Market & Deli has supported for two generations is a healthy lifestyle through products that promote positive and beneficial choices for the things we put into and onto our bodies. What began around Marlene’s kitchen table as a sustainable approach to living has blossomed into a community resource that is the foundation of a healthy way of life for thousands of individuals and families in southern Puget Sound. Smith herself seems possessed of lovely energy as well. Since opening Cafe Juanita in 2000, a whirlwind of glowing restaurant

Smith herself seems possessed of lovely energy as well. Since opening Cafe Juanita in 2000, a whirlwind of glowing restaurant  Smith’s holistic approach has served Cafe Juanita well, and it’s one that she cultivated during an externship in Ireland after culinary school. “Chef [Peter Timmins] was a master chef so everything was based on Escoffier,” says Smith, referring to George-Auguste Escoffier, a 19th century French culinary artist who was revolutionary in upgrading the culinary arts and fine dining experience, from recipes to service to kitchen environments to sanitation. “Proper technique and history were combined,” says Smith of Chef Timmins’ teaching. “It was great to work with such amazing raw ingredients–the best butter, wild game.” She continues, “The art of hospitality was also important. In Ireland, culinary schools teach front of the house proper service, so it isn’t just the chef’s perspective, but a guest-centric hospitality.”

Smith’s holistic approach has served Cafe Juanita well, and it’s one that she cultivated during an externship in Ireland after culinary school. “Chef [Peter Timmins] was a master chef so everything was based on Escoffier,” says Smith, referring to George-Auguste Escoffier, a 19th century French culinary artist who was revolutionary in upgrading the culinary arts and fine dining experience, from recipes to service to kitchen environments to sanitation. “Proper technique and history were combined,” says Smith of Chef Timmins’ teaching. “It was great to work with such amazing raw ingredients–the best butter, wild game.” She continues, “The art of hospitality was also important. In Ireland, culinary schools teach front of the house proper service, so it isn’t just the chef’s perspective, but a guest-centric hospitality.”

Good point. If any more people in the western Washington area loved Italian food, you’d never be able to get a table at Cafe Juanita. As it is, business is brisk, and growing. In fact, August 2019 was Cafe Juanita’s busiest month in the 19+ years it has been in operation, due in part to word of mouth recommendations and in part to a continued presence on culinary award lists. But Smith responds to the media attention and public demand differently than she did in the early days, when critical acclaim came at an almost overwhelming speed. In the first few years, Smith says, “It was not very enjoyable for me. As much as I was grateful and happy to be doing well and be appreciated, I found it all a bit too much. The constant feedback on sites like Yelp took me a long while to navigate.”

Good point. If any more people in the western Washington area loved Italian food, you’d never be able to get a table at Cafe Juanita. As it is, business is brisk, and growing. In fact, August 2019 was Cafe Juanita’s busiest month in the 19+ years it has been in operation, due in part to word of mouth recommendations and in part to a continued presence on culinary award lists. But Smith responds to the media attention and public demand differently than she did in the early days, when critical acclaim came at an almost overwhelming speed. In the first few years, Smith says, “It was not very enjoyable for me. As much as I was grateful and happy to be doing well and be appreciated, I found it all a bit too much. The constant feedback on sites like Yelp took me a long while to navigate.” Quality and sustainability are top priorities for Smith when sourcing ingredients. She looks for local and regional organic products that showcase the Pacific Northwest’s bounty, as well as sourcing Italian food and wine. In Cafe Juanita’s kitchen,

Quality and sustainability are top priorities for Smith when sourcing ingredients. She looks for local and regional organic products that showcase the Pacific Northwest’s bounty, as well as sourcing Italian food and wine. In Cafe Juanita’s kitchen,