Fewer work days start earlier than those of a baker, and the bakers at Winthrop’s Rocking Horse Bakery are no exception. In order to stack the cases with yeasted loaves like the Stehekin Seeded bread or the Sawtooth Sourdough, those working the ovens need to begin by dawn. By the time the bakery doors open at 7am, the air is rich with the scent of the breads, pastries, bagels, pizza, and other savory items that will soon be devoured by Methow Valley residents and visitors. Coffee is brewed, the counters gleam, and the Rocking Horse Bakery is ready for another day serving as a hub for sustenance, summits, and socializing.

Fewer work days start earlier than those of a baker, and the bakers at Winthrop’s Rocking Horse Bakery are no exception. In order to stack the cases with yeasted loaves like the Stehekin Seeded bread or the Sawtooth Sourdough, those working the ovens need to begin by dawn. By the time the bakery doors open at 7am, the air is rich with the scent of the breads, pastries, bagels, pizza, and other savory items that will soon be devoured by Methow Valley residents and visitors. Coffee is brewed, the counters gleam, and the Rocking Horse Bakery is ready for another day serving as a hub for sustenance, summits, and socializing.

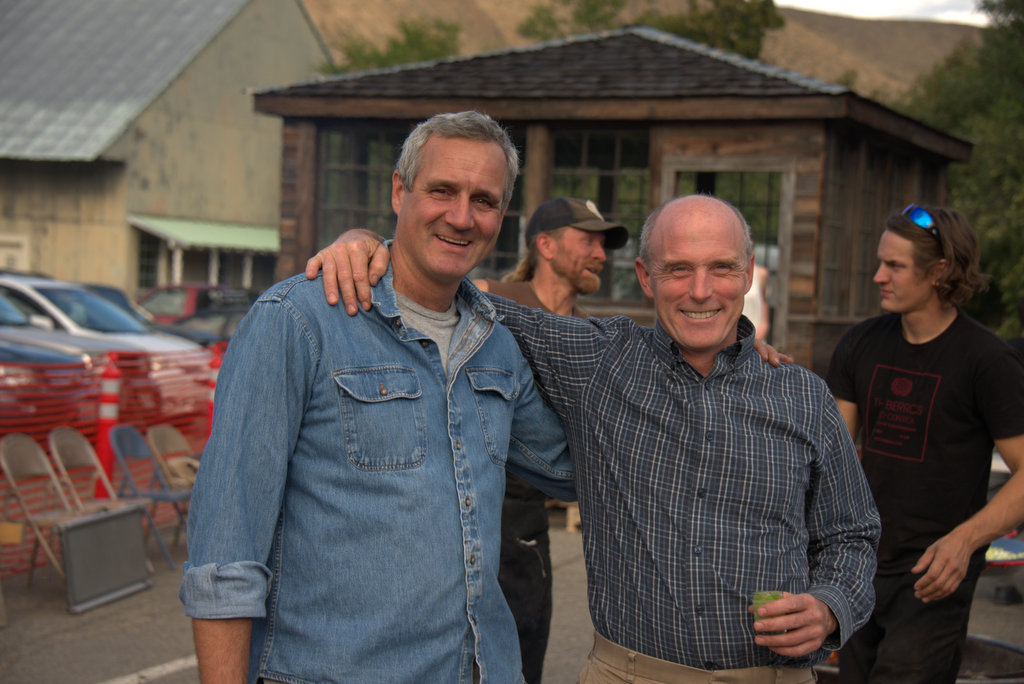

Rocking Horse Bakery was already a popular downtown institution when Steve and Teresa Mitchell bought it in 2010. At the time, the Mitchells were living in Vermont, but were exploring options for moving back west. When the Rocking Horse Bakery went up for sale, the Mitchells knew it was a good fit. Both had spent time in the Methow Valley throughout the 1980s-1990s and loved the outdoor recreation possibilities in the valley. The bakery was already viable and had good growth potential. Equally compelling were the demographic makeup of the valley and the opportunity for the Mitchells’ children, Kavi and Neela, to attend the Methow Valley Community School.

The Mitchells’ yin/yang skill set enabled them to hit the ground running when they took over the bakery. “We just dived right in,” says Teresa. Although Teresa’s background is in education, she was no stranger to the culinary world, and even owned a small business selling her own spice blends. In contrast, Steve has experience at every level of business, from manufacturing to retail sales. Their diverse but complementary backgrounds led them to the division of responsibility they currently enjoy at the bakery. Teresa manages the ordering, the baking, the books, the menu creation, and human resources, while Steve takes care of the front of the house, the equipment, and the building infrastructure.

The Mitchells’ yin/yang skill set enabled them to hit the ground running when they took over the bakery. “We just dived right in,” says Teresa. Although Teresa’s background is in education, she was no stranger to the culinary world, and even owned a small business selling her own spice blends. In contrast, Steve has experience at every level of business, from manufacturing to retail sales. Their diverse but complementary backgrounds led them to the division of responsibility they currently enjoy at the bakery. Teresa manages the ordering, the baking, the books, the menu creation, and human resources, while Steve takes care of the front of the house, the equipment, and the building infrastructure.

In the seven years since the Mitchells bought Rocking Horse Bakery, they’ve intuited which aspects of the bakery’s former life were important to retain, and which could be enhanced. One of the key relics from the previous owners is the sourdough starter, now 17 years old; it’s a component of many of Rocking Horse’s products. Another holdover is the use of Bluebird Grain Farms products. The bakery’s previous owners had used Bluebird’s freshly milled flours in several of their breads, and at the time Bluebird was the only locally-sourced ingredient in the bakery. Teresa preserved that tradition and has worked to incorporate Bluebird products into many of the bakery’s other mainstay menu items: pizza crust, bagels, and breads. “It has improved the quality of our products significantly,” says Teresa.

Bluebird products are also retailed in the bakery, along with 20 other local vendors. “Bluebird was our first,” says Teresa, “and it remains at the heart of our resale business.”

Bluebird products are also retailed in the bakery, along with 20 other local vendors. “Bluebird was our first,” says Teresa, “and it remains at the heart of our resale business.”

Teresa addresses the decision to fully commit to using Bluebird and other locally-sourced products. “It reflects our personal values,” she says, “using resources that are close by.” Teresa also recognizes that the local clientele–who sustain the bakery even when 2 out of 3 roads into the valley are closed–values local ingredients. “A lot of our menu development is specifically for the locals,” says Teresa, noting the adventuresome eating habits of local customers. “They’re very food savvy.”

Noticing what locals like has led to further development of the bakery’s savory menu. A number of the bakery’s savory recipes use Teresa’s custom spice blends, and she’s always looking for new ways to make the bakery’s popular soups and sandwiches. She has also developed new recipes around Bluebird’s whole grains, such as the bakery’s emmer biryani, a South Asian-inspired grain dish using Bluebird’s whole emmer-farro instead of the traditional rice.

Although Teresa is the chief baker in the family, Steve’s influence on the menu is apparent in the whoopie pies, whose origins, like Steve’s, are in New England. “We even import the fluff filling from New England,” Teresa says.

Although Teresa is the chief baker in the family, Steve’s influence on the menu is apparent in the whoopie pies, whose origins, like Steve’s, are in New England. “We even import the fluff filling from New England,” Teresa says.

Longtime visitors to the Methow Valley may recall Rocking Horse Bakery in its former location, one door north of its current venue. “We used to look through the window of the current space when it was a real estate office,” says Teresa, “and covet it.” Serendipitously, that space became available in 2013 and the Mitchells built it out and moved in. “We only closed for 2 days for that move,” says Teresa.

With its high ceilings and fun, funky decor, the “new” bakery space is not just a place to fill your stomach, but it’s also the site of countless meetings, planning sessions, impromtu reunions, board recruitment functions, and even job interviews. On slower days, some locals are known to park themselves at the bakery and work remotely all day. “We love all the different ways our customers use the bakery,” says Teresa (although secretly I wonder what she thinks of the occasional visitors who plant themselves at a table and stream movies for hours, taking up bakery bandwith). It’s a comfortable space, with great light and good acoustics; it’s no wonder Rocking Horse is one of the valley’s preferred gathering spots.

The bakery has been somewhat of a family venture over the years, with the Mitchell’s oldest, Kavi, working at the bakery counter since he was 14 and his younger sister, Neela, helping with big events and some of the artistic aesthetic of the space. Still, despite the year-round demands of the bakery, the Mitchells get out on fantastic trips with their kids. “We prioritize travel,” says Teresa. “Our kids [both adopted from India] are products of the world, and we want to expose them to the great wide world and different ways of living.” Teresa expresses gratitude that through international travel, her kids have cultivated a passion for art and culture.

The bakery has been somewhat of a family venture over the years, with the Mitchell’s oldest, Kavi, working at the bakery counter since he was 14 and his younger sister, Neela, helping with big events and some of the artistic aesthetic of the space. Still, despite the year-round demands of the bakery, the Mitchells get out on fantastic trips with their kids. “We prioritize travel,” says Teresa. “Our kids [both adopted from India] are products of the world, and we want to expose them to the great wide world and different ways of living.” Teresa expresses gratitude that through international travel, her kids have cultivated a passion for art and culture.

Along with travel, the Mitchells somehow carve out time for other passions, such as Steve’s photography business, Mitchell Image. Kavi graduated from high school in early June, so they’re taking him to start college in Colorado in the fall. Oh, and their head baker is on leave. “It’s crazy times,” says Teresa. “Luckily we both have good endurance.”

Visit the Rocking Horse Bakery next time you’re in Winthrop, at 265 Riverside Ave.

Bremerton is abuzz about

Bremerton is abuzz about  It’s this acceptance of the appropriateness of “sin” in food that makes Saboteur’s cafes such welcoming places. “I don’t preach about ingredients,” Tinder says. “I present the food the way I believe it should be presented, and then we treat people with respect and let them make their own decisions.”

It’s this acceptance of the appropriateness of “sin” in food that makes Saboteur’s cafes such welcoming places. “I don’t preach about ingredients,” Tinder says. “I present the food the way I believe it should be presented, and then we treat people with respect and let them make their own decisions.” Tinder learned of

Tinder learned of  Some of the time to figure out new programs and next moves comes during the biannual bakery closures–once in the summer and once in the winter. They travel a bit, visit old friends in California, and then head back to Bremerton to work. “I do a lot of brainstorming in my head and on paper,” Tinder says. “Saboteur is a small business and I can’t afford to just buy a bunch of expensive ingredients and experiment. But I do pretty well with the preliminary stages happening on paper.”

Some of the time to figure out new programs and next moves comes during the biannual bakery closures–once in the summer and once in the winter. They travel a bit, visit old friends in California, and then head back to Bremerton to work. “I do a lot of brainstorming in my head and on paper,” Tinder says. “Saboteur is a small business and I can’t afford to just buy a bunch of expensive ingredients and experiment. But I do pretty well with the preliminary stages happening on paper.”